Agricultural markets driving up poverty in the global south

Hello and welcome to the latest edition of The Balanced Economy Project’s Counterbalance newsletter. This week, we’re taking a look at food insecurity in a major African economy.

If you read last week’s edition of The Counterbalance, you will know one of my early promises was to look at the fight against unfair monopolies and concentrated markets through an international lens.

You may also recall that I said learning about monopolies and competition helps you to understand why food prices are so high. This week I try to combine both of these points, as I look at uncompetitive food markets that are driving up poverty rates in one of Africa’s largest economies.

According to a recent market inquiry conducted by the Competition Authority of Kenya, poultry and dairy farmers in the country are paying much higher prices for animal feed — the food used to feed livestock — compared to international markets. For example, between the years 2021 and 2023 Kenyan poultry farmers paid an eye watering 54% and 42% higher rates than their Brazilian and South African counterparts.

The inquiry, published earlier this year, found that very few large animal feed producers make up the majority of commercial feed in Kenya, with the largest four suppliers accounting for “well over” half of commercial sales. Specific to poultry and dairy feeds, specialised producer companies account for roughly three quarters of Kenya’s national supply.

Let’s pause for a moment: you may be reading this having never thought about food prices in Kenya, and thus be tempted to ask yourself: why does this matter?

The Shamba Centre — an organisation which aims to achieve a world without hunger and which supported Kenyan officials in the inquiry — points out that these market conditions translate to Kenyan households paying higher prices for essential food products, in turn undermining food security in East and Central Africa’s largest economy and devastating those who live under the poverty line.

“If you increase the price of poultry, for argument’s sake, by 20% around the world, the impact on a US household is proportionally much less than the impact on a low income household in the global south, where their food spending is a much greater share of their income,” Simon Roberts, a Competition Economics Professor at the University of Johannesburg told me.

But the inquiry also serves as a reminder of a broader problem, which disproportionately impacts the global south. Like Mexico’s struggles after the gutting of its competition authority that we mentioned last week, Africa’s weak capacity across its countries’ competition watchdogs makes it near-impossible for the region to guarantee fair food and agricultural markets.

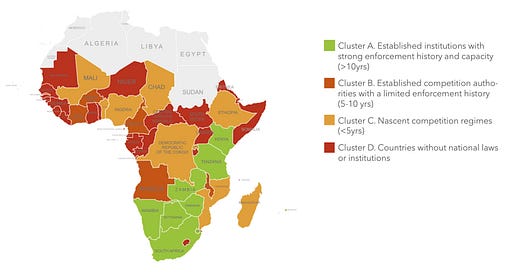

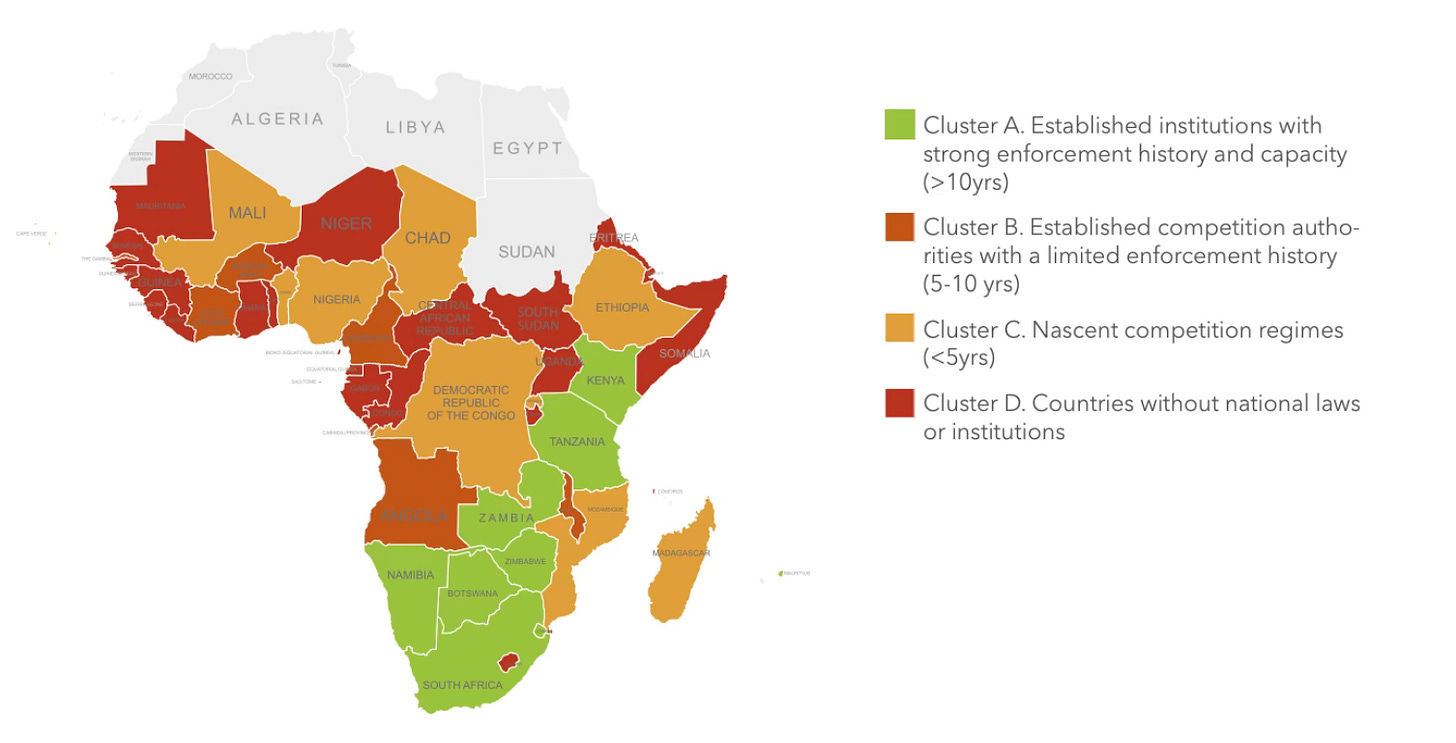

In a separate report on the competition landscape in sub-Saharan Africa, the Shamba Centre noted that 22 out of 48 countries do not have national competition laws or institutions in place to enforce a competition regime.

Only nine countries have laws and institutions that are over a decade old, equal to the number of countries with nascent competitions regimes but no competent authority to enforce those laws.

Africa’s continent-wide struggle to maintain a fair food and agricultural sector also brings me to an important point about established anti-monopoly discourse.

Economists like Isabella Weber have done great work linking monopoly power to price surges in the food and energy sectors, but broadly speaking, monopoly discourse today is dominated by — and revolve around — conversations about technology.

The rise of tech giants including Google — which is currently embroiled in antitrust cases in Europe and the United States — has prompted many in this space to think of monopolies primarily within the context of tech or nascent sectors.

But in reality, monopolies and uncompetitive markets harm sectors that impact our basic necessities and the broader cost of living — and as Kenya’s story demonstrates — often with disastrous results for those living close to, or in poverty.

As revealed by the Shamba Centre’s sub-Saharan report, agricultural and food markets in Africa are “particularly vulnerable” to non-competitive conduct because they are often the smallest by sector, requiring large amounts of capital to enter. This translates to weak market conditions that fail to protect small businesses and consumers.

“We need to be paying a lot more attention to food and agriculture, one because it’s such a vital part of the cost of living, and two because there has been a huge increase in concentration in food and agriculture markets around the world,” Roberts also said.

Weekly highlights:

Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom — a law firm best known in Brussels for representing TikTok owner ByteDance — recently committed to providing “at least $100 million” in pro bono legal services in a deal with the Trump administration.

The European Commission this week launched an informal inquiry into Italy’s application of investment screening rules to domestic bank mergers. The probe could have potentially far-reaching consequences for Italy’s “golden power rules”, which allow the government to block foreign investments and mergers in the finance sector.

A brief note on AI: muckrakers at POLITICO revealed this week that the European Commission is finalising a plan to “streamline” rules governing artificial intelligence, in an effort to accommodate concerns communicated by big tech and AI firms. The draft plan arrives as Europe plans to unveil a strategy that would turn the Bloc into an “artificial intelligence continent”, and comes just days after President Trump’s slew of global tariffs sent shockwaves through global markets.

I’ll finish this section with a look back to last week, when the head of Spain’s National Markets and Competition Commission Cani Fernández Vicién said antitrust agencies should be more open-minded and less risk averse.

Soundbite of the week: In case you missed it…

Last week, Executive Vice-President of the European Commission for a Clean, Just and Competitive Transition Teresa Ribera came to the defence of the Digital Markets Act.

Speaking at an Atlantic Council Front Page event in the US, Ribera stood firm against recent comments made by Federal Trade Commission chief, Andrew Ferguson, about European firms “levying taxes on American firms.”

“We’re open to clarifying any misunderstanding, but I am sure that when the US government takes a decision in terms of ensuring enforcement of American regulations or tax, they do not pay attention to the origin of the company they are taxing, they pay attention to where they work, and where they get their profits,” Ribera said.

Read the full story here.

Data section: Soybeans in the crosshairs

Europe and the United States are inching ever closer to a full-blown trade war as European Commission decision makers consider imposing tariffs of up to 25% on swathes of US exports.

According to an internal document seen by POLITICO, the EU is considering subjecting US goods to tariffs ranging from 10% to 25%. in response to The White House’s move against steel and aluminium.

Here are the most valuable individual categories of US goods in Europe’s crosshairs, starting with soybeans.

The Counterbalance is published every Thursday. Please send any thoughts and feedback to scott@balancedeconomy.org.