Welcome to The Counterbalance, the newsletter of the Balanced Economy Project.

[Update: Michelle’s and Simon’s paper, “A sustainable future: how can control of monopoly power play a part?” has now been published in the European Competition Law Review.]

Introduction

In November 2018 a French "Gilets Jaunes" (Yellow Vests) protestor posed a raw and uncomfortable question for the climate movement. "The elites are talking about the end of the world," the protester said. "But we are talking about the end of the month."

Their paycheques, in other words. The immediate trigger for the protests was President Macron's fuel tax increases, which aimed to help the green transition, but which would hit the poorest hardest. At a deeper level, the protests reflected a malaise now afflicting all western democracies: a sense that the poor are getting shafted, while wealthy elites party.

Tackling climate change will be immensely expensive: some $4 trillion a year in clean energy investment alone, according to the International Energy Agency. There is no way the poorer sections of society will tolerate paying for that.

Through the other end of the telescope, another uncomfortable truth emerges. To put it crudely, poor people vastly outnumber rich people, and they spend more of their income on fuel. Economic justice would likely spur relatively large numbers of poorer people to spend a relatively high share of the additional income on heating and transport. This would not be remotely compensated by the reduced spending of (far fewer) rich people, each with less economic incentive to cut back on their holiday flights to Martinique. So economic justice alone could boost fossil fuel consumption.

As I argue elsewhere, the twin struggles for climate justice and for economic justice, must be tackled together, as a package. If we pass the climate transition costs onto the shoulders of poorer sections of society, it will worsen popular anger, and create more fertile terrain for conspiracy theorists and demagogues who would overturn the climate movement. Of course, this is already happening.

The climate movement is already criticised for being trapped in a "white, middle-class ghetto" — watch Michaela Coel's smash hit BBC/HBO drama I May Destroy You, to get a racially charged perspective on this uncomfortable truth.

So the economic justice movement and climate movement must figure out clever ways to work together. Proposals such as carbon dividends would be a good, clear example. But can competition policy play a role?

Our answer is short: yes, yes it can.

At a most basic level, we believe that concentrated power embedded in our economies blocks the systems change needed to realise many desirable societal, democratic, and environmental goals. If we don't address this power, we will remain caught in the powerful gravitational pull of dominant firms - such as large energy companies - with room only to act at the edges of their power. Competition policy is potentially the most powerful tool available, to restructure our economies in the public interest, to break and disperse this power and unlock the potential for change.

A first, general problem is that this competition policy tool has fallen prey to a worldview, defended by a technocratic competition establishment, which has on balance encouraged monopolisation and concentration of economic power, around the world. (We have written extensively about this.)

But when it comes to climate, there are more specific problems too.

For example, let's say three companies make competing widgets. The first merrily pumps carbon dioxide into the air. The other two instal expensive carbon capture and storage technology (CCS). Of course, the first, dirty company has lower costs, so it will likely win the competitive race and take over the market, without outside intervention. This is an example of "harmful competition," where bad actors become dominant (and this tends to foster other abuses.)

One response to this problem - which in a limited way has the European Commission's favour, involves relaxing competition rules in certain circumstances, so that actors who might otherwise have been prohibited from cooperating under anti-cartel rules, may do so. The three widget-makers here would cooperate under an officially-sanctioned cooperation agreement to instal CCS. Indeed, subject to various strict conditions, Austria has introduced an exemption into its domestic competition laws (i.e. those local situations that aren't covered by EU competition laws) where an anti-competitive agreement is allowed if it "significantly contributes to an ecologically sustainable or climate-neutral economy."

Is this a good approach? To relax competition laws, to reach sustainability goals?

It might be. But imagine the widgets are for machines that make baby formula. Our sustainable widget agreement may lead to greener but more expensive baby formula: we may have an economic justice problem.

The Commission tries to ensure that such cooperation exemptions from competition law are narrow, to prevent abuse. But monopolists can also be masters at putting crowbars into new openings, using their market power to increase their profits beyond what the fundamentals justify.

So we at the Balanced Economy Project do not endorse or oppose this general approach: it may be justifiable in some cases, but it may also be open to abuse. At the end of the day, though, we are seeking stronger medicine. Can we tackle both monopoly power and climate change, directly, and at the same time?

Well, our co-founder Michelle Meagher, currently on maternity leave, has just co-authored a paper on this topic, entitled A Sustainable Future: how can control of monopoly power play a part? Balanced Economy’s Nicholas Shaxson spoke to her co-author, Simon Holmes, a visiting Professor in law at Oxford University, a Judge at the UK's Competition Appeal Tribunal, a legal adviser to the NGO ClientEarth, and the author of seminal papers in this field.

Although the Balanced Economy Project does not necessarily agree with every one of Simon’s positions, there is an awful lot of common ground, as the following interview makes clear.

Interview: European competition policies and the climate.

NS: Hello Simon. I'm just looking at a European Commission document called "Competition policy in support of Europe's Green Ambition." In trying to achieve sustainability, it alarmingly insists "that antitrust enforcement remains anchored to the consumer welfare standard." We have long argued that focusing excessively on consumers has airbrushed power out of the equation, and also concepts such as sustainability and the broad public interest - with terrible implications. What gives?

SH: I have three issues with the so-called "consumer welfare" standard. First, it is not what our law says: it is not in the treaties, and has never been endorsed by the European Courts. Second, for the most part, we have perfectly good laws and we should focus on what they do say-and not on something that they don't say. And third, if "consumer welfare" was what the law said, it could be a perfectly sensible standard. Look it up in the dictionary: it's about "the health, happiness and futures of a person or group" and synonomous with "well-being and good health". It's not just about prices, profit or fortune - and still less about maximising output. It's quite capable of encompassing concerns like having clean air to breathe; producing goods using fewer resources; having enough food to eat - and many other facets of economic justice.

So, while we make some suggestions in our paper for changes to the law, one of its main points is that we already have most of the tools that we need to tackle these problems - we just need to use them in more intelligent ways.

NS: What are these tools?

When it comes to tackling monopoly power while promoting sustainability, existing European competition law (and its national equivalents) have three main elements.

The first is Article 101, which prohibits "anti-competitive" agreements between independent market players. Next is Article 102, to prevent dominant actors from abusing their dominance.

A third strand was added later, in 1990: merger control. We were letting companies get bigger and bigger, then seeing if we could prevent them abusing their dominant positions after the horse had bolted. With merger control, we could nip that in the bud.

NS: So how do we use the existing tools better, in a climate context?

SH: Two of the central purposes of competition law are to prevent monopoly power arising - that is merger control - or to prevent that power being abused. The current laws can do a lot more, on both counts.

First, the "abuse of dominance" provisions under the EU's Article 102 (and its national equivalents) can be used to attack unsustainable practices - because there's a lot of overlap between something that would be an unsustainable practice, and something that would be an "abuse" of a dominant position. The barriers to us doing that occur where people take an overly narrow or cautious approach to those laws.

Take something like unfair pricing. In our article, we go back to basics and say, "what is the normal meaning of an abuse?" What would the man or woman in the street think is an abuse? Well: something that is very unfair, or particularly unsustainable. For example, when dominant buyers of primary products (such as coffee, cocoa or bananas) pay an unsustainably low price to farmers - with the result that farmers cannot feed their families, and over-exploit the land in a desperate attempt to scratch a living.

This is unsustainable, both in the environmental sense, where there is not enough money in the system to produce food on sustainable basis, and more and more land must be cleared to produce food -- but also in a wider sense: people aren’t getting a fair wage or income.

But it is also what most people would instinctively see as an abuse. Yet many in the "competition law bubble" have difficulty seeing it as an abuse.

NS: Why this disconnect between the competition bubble and the real world, in this context?

SH: Well, we are often talking about two sorts of abuse, "exploitative" and "exclusionary".

Any normal person would naturally think of exploitative abuses. A monopolist can exploit consumers, can exploit resources, in ways that most people would think of as abusive. And in fact in the law itself, Article 102, three quarters of the examples given are exploitative! There is a strong connection between people’s normal sense of justice, and what is actually in the law.

This is important in the area of sustainability, as many unsustainable activities are exploitative.

But what has happened, in practice, is that competition authorities have focused instead on "exclusionary" abuses, which is where dominant companies use their muscle to exclude competitors and close down competition. This is all about whether competition is working properly or not, rather than whether there is exploitation. The theory is: if there is competition, then all will be right in the world. If prices are too high, then if you ensure competition, competitors will rush in, prices will fall, and this will take care of the problem.

But take the example where a large company offers a complex set of discounts-effectively lowering prices. Competition authorities often fear this may push competitors out of the market and therefore outlaw it as an "exclusionary" abuse of dominance. But the person in the street, by contrast, might have a hard time seeing low prices as an abuse-indeed he/she may simply see it as a welcome bargain.

I'm not saying that exclusionary cases are wrong. They are often right. I am just saying that we've got the balance wrong. There is scope to bring more exploitative cases against unsustainable practices perpetrated by dominant companies.

NS: Liza Lovdahl Gormsen's case against Meta/Facebook takes a swing at exploitative abuses. I'm sure you can't comment on that. But why has the competition law bubble lost sight of exploitation, and focused on the functionings of competitive processes?

Well, there are positive reasons, and negative ones. On the positive side, if you prevent dominant firms from unfairly locking up markets and excluding competitors, that is likely to be a good thing. But even then, markets don't always correct, even when there is competition. For example, if purchase prices are artificially low, as in my previous example, will competitors rush in and provide, what, higher prices? I think not!

Also, there is a the reluctance to pursue exploitative abuse cases - because they are difficult. Say there is an exploitative excessive pricing case. What is an excessive price? How do you measure that? Competition authorities are reluctant to be seen as price regulators. They have to be careful.

I could add a third dimension. The Commission's guidelines on its enforcement priorities which is the bible that people use for abuse of dominance, only covers exclusionary abuses!

Why? Well, for the sort of reasons I’ve given, but also, there wasn’t sufficient agreement on what to write about exploitative abuses. The then Director-General at the Commission took the decision to put something out on exclusionary abuses, and I think the intention was to put something out on exploitative abuses later. But that was back in 2009: 13 years later it still hasn’t happened.

NS: So to summarise, under Article 102 (abuse of dominance) we should frame many climate-abusive economic activities as "exploitative". That not only fits with ordinary people's natural sense of these abuses, but the treaties themselves emphasise this. So there is no legal obstacle to us re-balancing our enforcement in this direction. If we do, we can achieve a lot against climate change. And by the way, a re-energised focus on exploitative abuses could also achieve a lot from an economic justice perspective too. Is this about the size of it?

SH: Yes. It seems that the question is not so much whether we can use Article 102 to attack these abuses as exploitative - we clearly can and must - but whether there is the political will do do so.

Civil society and injured parties must play a part here, bringing cases to the attention of the competition authorities or courts. And both the latter must be willing to take them, and look at Article 102 with fresh eyes. This is essentially what Part II of our paper is about.

NS: So: about merger control. We at the Balanced Economy Project are constantly outraged by the fact that over 8,000 mergers have been notified to the European Commission since 1990, and that only 30 of those have been outright blocked. That is a shocker - matched perhaps by the scandal that almost nobody in the media, political parties, or civil society has raised a stink about it. Anyway, I like to think that strengthened merger control could both promote economic justice and climate justice. Am I right?

SH: Yes. We have a whole section of our paper on that: Part III. Mergers are a hugely profitable — and thus politically sensitive — area. But given the scale of the crisis, we can and must use the tool.

Our starting point, and this is particularly where Michelle comes in, is the sheer scale of the recent concentration and market power and the harms those are causing - and the increasing evidence that mergers, which are largely being approved, bring few benefits, except usually to the shareholders of the target. And there is no positive "right" to merge or to be "big". So we shouldn’t be afraid to use our merger policies. We have a serious problem of under-enforcement.

How can we use merger control?

Well, for one thing, European authorities use a test called "significant impediment to effective competition" (SIEC), to assess mergers.[i] Included in the SIEC criteria is this: "development of technical and economic progress provided that it is to consumers' advantage." Well, 'technical and economic progress' seems to be very capable of taking into account the sustainability effects of a merger – especially related to climate change.

If you produce greener, more sustainable products, that is to my mind "economic progress", it is not just about price. And our paper goes into detail about a number of factors that support this view. For example, we have spoken about the heavy focus on consumer welfare, which involves both quality and price - and of course a more sustainable product is a higher quality product, other things being equal.

Of course if a more sustainable product is more expensive, then there is a balancing act here.

NS: I see in your paper, you have a section entitled "Updating the law - some more radical approaches." Please do tell!

SH: Well, as we said in the paper, there will be howls from the multi-trillion dollar M&A industry.

I have spoken so far of ways that existing laws can be used. But this might not be enough, given the scale of the climate problem. We offer three basic ideas.

First, we need to look at so-called "killer acquisitions" where big firms acquire smaller producers of green products. Killer acquisitions are often done to snuff out competition, and the effect is often to harm innovation. [This is not actually new: the EU's Green Policy Brief does mention this concern]. We are not saying all acquisitions by big companies of small ones are bad for a green policy. They may even be good - for example, where a small company's green techniques are applied across the big company’s much bigger production. We are saying that they should not escape scrutiny completely, which is often the case at present.

Second, we should have new sustainability or climate criteria in merger control.

We have proposed a new provision which would require the Commission to take "all appropriate measures to ensure that the concentration [ie the merger] has no adverse effect on climate change and environmental sustainability". This would complement the competition assessment.

The third way concerns the burden and standard of proof. Currently, the competition authorities have to prove that a merger will be harmful, if they want to block it. With so few deals being blocked, we think there is scope to consider: a) should the burden of proof be reversed, so that the merging parties need to prove that there would be no harm; b) what should standard of review be, and c) what should the parties have to prove?

We have thrown out all sorts of ideas here. Michelle and I don’t actually agree on which is the most appropriate: we present them as ideas. She goes a bit further than I do.

I think it would make sense in relation to our proposed climate change and sustainability provision to require the merging parties to prove to the Commission that the merger has no adverse effects on climate change or sustainability. That already strikes me as pretty radical.

But Michelle goes further: our final suggestion would require the parties to prove that the merger will have a positive impact on climate change and sustainability, for it to go ahead. That suggestion will be a complete anathema to most people on the lucrative M&A merry go round. Michelle accepts that that would kill M&A activity-but it’s no secret that she is pretty radical on one or two things!

[i] The UK and US use "substantial lessening of competition" or "SLC" - but for present purposes they are essentially the same thing.

ENDNOTES

Capacity building training on Competition Policy, Amsterdam, Sept 15-16. By Balanced Economy Project, Article 19, and University of Amsterdam. The programme is full, but we plan to hold more training events in future. Please get in touch if you would like to know more.

Big is bad not so much because it hurts consumers, but for a wider range of reasons, including that it becomes ungovernable, or it often treats laws as 'recommendations' only. Offering an overview, and solutions.

The world needs U.S. antitrust legislation: Big Tech must not determine global human rights - Access Now. International support for US antitrust policies.

To Level Up, Tackle Monopoly Power - Balanced Economy Project

For a UK Labour Party outlet. If we move beyond dictionary definitions of 'monopoly,' we will realise that monopoly power is all around us — and we potentially have more power to act than we may think.

AGENDA 2025: Time for a Comeback? The Case for Structural Antitrust - Dkart

A view from Germany, which notes a slowly shifting mood. From a participant in our recent Rebalancing Power event in Berlin.

UK Tribunal agrees that Meta’s acquisition of GIPHY harms competition - Privacy International

A rare example of civil society intervention, in a crucial and super-rare case to block big tech acquisitions. A small but significant victory. See our assessment here.

The outgoing head of the UK's Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has been a force for good, standing up to powerful and often dark forces swirling around him. Alongside the departures of Rod Sims from the Australian competition authority, Isabelle de Silva from the French competition authority, and threats to the green shoots of US antitrust from the coming midterm elections, the movement now faces significant headwinds. A common factor in each country (except to a degree the US) has been a lack of civil society engagement. That can, and will, change.

Monopolies killed my home town

A Canadian podcast, which among other things looks at the incoming Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project (CAMP,) and the kind of competition that makes an ecosystem, like a forest, stronger, and keeps the whole forest in balance.

ICYMI: in case you haven't seen these shocking whistleblower files yet. Where to start? We will highlight the dubious role of former EU Competition Commissioner Neelie Kroes.

How a Barcelona minnow defeated a global platform (for now) - Gig Economy Project

A union “threatened to go to war” recently, and has won major concessions.

How a £3.8 Billion Merger Will Redefine Central London Restaurants - Eater London

This power will allow them to choose dishes, markets, menus - and who to let in to the fiefdom. "And so goes homogenisation."

Inside the secret, often bizarre world that decides what porn you see - Financial Times

"The adult industry’s de facto regulator isn’t government, international convention or business itself. It’s Mastercard and Visa."

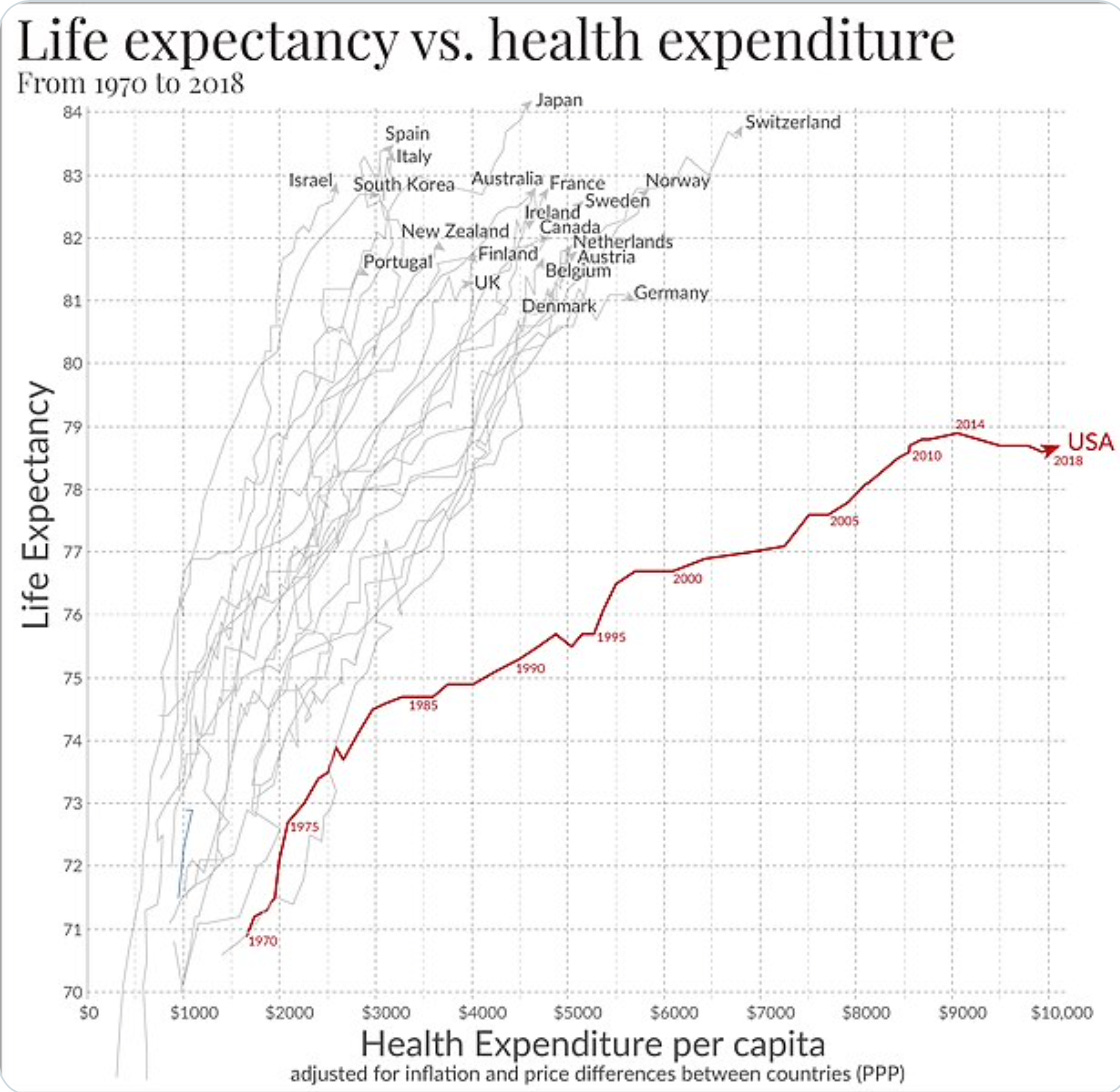

A chart, to end. Heavily monopolised private healthcare, versus largely public healthcare.