Welcome to the third edition of The Counterbalance, a newsletter from a new anti-monopoly organisation, the Balanced Economy Project (which we’re just setting up.)

This edition focuses on an interview with Tommaso Valletti, who served as Chief Competition Economist at the European Commission from 2016 until 2019. He tells us how, after moving from academic life to policy and being confronted with questions of political power and democracy, he had to take a stand. In this interview with Balanced Economy’s Nicholas Shaxson, Valletti reveals much about the rather corrupt interlocking system of monopoly in Europe, and offers ways forwards: one big, meaty solution in particular.

NS What was it like moving from academia to a position of power?

TV I am an academic, an expert in industrial organisation. The academic approach is to find trade-offs, ‘on the one hand this, on the other one that, let’s do more research and gather more information.’ In the policy field, you don’t have that luxury. You have to make choices in finite time, taking risks. For instance, if you wait for ultimate proof that a mask is useful [to fight Coronavirus], it may be too late.

I saw the consultants hijack a certain way of doing economic work. They do this on a massive scale, to create doubt. They bombard you. They say ‘well, this merger could bring all these fantastic efficiencies: here is a possibility you should consider.’ You know that in practice this will not play a role, but then you have the burden of proof as an authority to dismiss those claims. It is a very dirty game.

NS: You had an awakening, how was this from a personal perspective?

TV I live in the UK, and I see all these people in position of power coming from doing PPE [Politics, Philosophy and Economics] at Oxford University or similar. They are trained in the debating societies to argue anything, and the opposite, within 5 minutes. They are very eloquent. When I first came to the UK, I thought, as an academic, ‘how interesting, how witty, how intelligent!’ But it has actually been devastating. Because economic power will take exactly those kinds of people, then put them in front of a judge, or the Commission, and they will create smoke around an issue.

These people have lost the sense of who they are. I witnessed that, and it made me re-think my own values. This is not about some narrow economics. It’s about democracy, about economic and political power.

I had avoided this for too long. I had to ask myself, after having studied markets for over two decades: what do I have to say? Where do I stand? What is right, and what is wrong? That was my re-awakening.

NS: Did a particular case or event crystallise this?

TV My first big cases involved Dow-Dupont, and Bayer-Monsanto, in the agrochemical business. We found a very interesting angle, a bit overlooked, that those mergers may reduce innovation.

There was immediately all this negativity coming from the economic consultancies, and the law firms. Baker Mackenzie, a law firm on the side of Big Pharma, tried to rebut us. They first sent their lawyers, who were not smart enough to tackle good economists. So they hired consultant economists, but the consultants didn’t have the same tools we had. We were pretty robust.

So they escalated. They went to people in Toulouse, at Bocconi, in Bologna, paying them to come up with some second order effects, some details, to undermine our results. There were conferences, symposia, and round tables, saying how crazy we were trying to gaze into the “crystal ball” to predict the future. There were personal attacks.

Beyond these cases, economics in antitrust uses standard models, often static and with assumptions that are borderline heroic, if not just wrong. In economics, we like to think consumers are rational agents making informed choices on the best information. But this cannot be the starting point in concentrated markets. Take Big Tech as an example. The idea that you first collect all the available information on the web, then make choices, well, this isn’t how people behave. People just click on the first thing they are shown.

NS What is the machinery of monopoly in Brussels?

TV Obviously Brussels is full of lobbyists, think tanks and people who never disclose that they are working for the companies.

The gatekeepers are the law firms. Clients establish relationships with big law firms, and these relationships continue over time. The big law firms instruct the consultants about what they have to say. The economists who serve them are just useful fools.

With Dow-Dupont or Bayer-Monsanto, some of us, lawyers or economists, had to become experts in agrochemistry. We had to ask for information. There is a lot of knowledge that enforcers don’t have, especially in novel industries. But I could never talk to a scientist. Instead you would talk to a lawyer who had already filtered the information.

As another example, I was working on Qualcomm, and there were some excellent academic economists from Toulouse who had produced a model for the parties. I knew them already, and we had a meeting between peers. But any time I asked, ‘Patrick, but if you change this assumption, doesn’t it change the result in this way?’ immediately the lawyer would say ‘don’t answer that question.’ It was like a role-playing game, a preset game, in which I could not participate without talking through the lawyers.

NS Can you name these gatekeepers?

TV That’s easy. There are basically three economic consultancies: Compass Lexecon; Charles River Associates (CRA,) and RBB. There is a fringe of less relevant ones. It is very few law firms, for example Freshfields, Latham and Watkins, Cleary Gottlieb, Skadden, Linklaters, Clifford Chance and others.

Not everything they do is bad, of course. But this legal mentality has proved toxic. They will do anything for money.

NS Were there alternative powers or voices pushing back? Like small businesses, or non-governmental organisations?

TV Almost never. In a few cases, as with Google, you might have relatively smaller firms as complainants. Specifically, I never had any contact with NGOs. I was never asked. Take for instance the recent interest in monopsony, the idea that market power may have negative impacts on workers and wages. But I was never, not a single time, invited to discuss the outcomes of potential mergers or antitrust investigations with representatives of the unions. These people are completely missing. And forget about startups. They are busy innovating, they are small, lean, and hungry, working 24 hours a day: they have no clue how to lobby, they don’t have policy people.

But this bubble has recently become a little more open. In the Google-Fitbit merger, for example, Amnesty International came into the debate, privacy experts came in, beyond the usual people. This is a good development.

NS What role do the courts play?

TV The courts are independent of the Commission: you have the ECJ (European Court of Justice), the general courts. That is fine: it’s the system of checks and balances.

But there is a legalistic culture within DG Comp - the Directorate-General for Competition - which is extreme. There is stigma attached to losing cases in court, of having decisions reversed. The stigma is so bad that basically it freezes people from taking novel approaches. But you have to push the boundaries, especially with new markets, and Big Tech in particular. If you never take risks, the consequences are clear: market consolidation, and market power. If you are not losing cases in court, you are not being ambitious enough.

Also, especially in the US, the courts’ judges are trained by think tanks that teach them “The Economic Truth” with courses in simplistic economics that last 5-6 days at most. They always project the view that markets are efficient. These centres, these think tanks, like the Global Antitrust Institute [at George Mason University], and the International Centre for Law & Economics, they are funded by the Koch brothers, by the Googles and the Facebooks, they don’t disclose, and they basically brainwash generations of judges.

These centres don’t do scholarship. But they represent themselves as repositories of economics knowledge, which they don’t have. The judges cannot discriminate between what these guys tell them, and what reputable academics might tell them, also because these academics too often stay in their ivory towers. There are good academic papers published in good journals, then consultants come up and say ‘No, Professor So-And-So is wrong’, here, I have written it up.’ They produce a glossy pamphlet with three nice pages: exactly what the judge needs, he can say ‘ah, here is a counter-argument, here is an anecdote to rebut this. So, nobody knows’.

This goes on, all the time.

NS If you had to offer one big solution, what would it be?

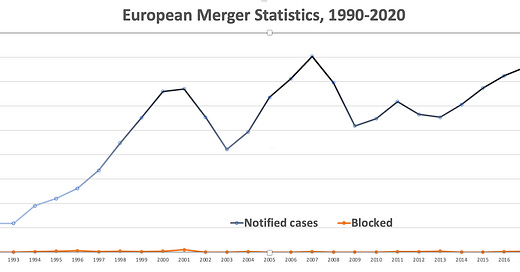

TV Mergers are not the only problem, but they are the starting point of consolidation and possible abuses. Mergers are almost never blocked. Think of the numbers. In Europe every year there are about 15,000 mergers, mostly tiny stuff, and we let it go. They would maybe notify 400 transactions [to the Commission] every year: of these, maybe 30 go into a deep assessment, maybe 15 get some remedies, and often none are blocked.

The GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) have acquired more than 1,000 firms in the past 20 years, and zero of those transactions have been blocked -- and 97 percent were not even assessed by anybody. These are extreme, ridiculous numbers.

During my tenure of three years I contributed to blocking the merger of the LSE (London Stock Exchange)with Deutsche Börse, Alstom-Siemens, Tata-Thyssen-Krupp in steel, and others. In almost two years since I left, we have had zero. Nothing has been blocked since I left, even Google-Fitbit.

The process has become crazy. You must create a definition of the relevant market, then calculate market shares. This will often have little to do with reality. For example, with Facebook-Instagram, the outcome of the investigation into what is the relevant market was: Online Camera Apps! You have commissioners, enforcers, consultants, debating for hours and hours and hours and hours. This burns resources.

The Chief economist team which I was heading had 30 people: that’s it. Google, Facebook, or Amazon could put hundreds of people onto every case.

So: how do we deal with this?

Well, there is lots of strong economics saying that once you are a large company, further concentration does not create further benefits. And I do take the view that big is bad, because concentration is political power, it is corruption, it is a risk to democracy. We have lost this idea, and instead the economists are enamoured with “efficiency.” If size was everything, if big was efficient, then the Soviet Union should have won the Cold War.

Let us go back to a more structural approach that we have abandoned.

When firms are super-big, I would start from the structural presumption that ‘I don’t want you, the companies, to merge.’ I block it. But then I pass you the ball. Because the authorities don’t have the information: the merging parties do. So I say – and this is the reversal of the burden of proof, which is rebuttable – ‘can you prove that this merger is the only way to bring these benefits?’

I would say “You, Google, the most almighty firm in the world, why do you need to purchase Fitbit to achieve these benefits? Can’t you do it yourself, with all the smart guys you have? And leave Fitbit on its own, or available for purchase by someone without your market power, as this will increase competition? Prove that you really cannot do it without buying Fitbit. It is beyond my comprehension. Show me.”

If you do that, the debate changes completely. They will bring the data that we never had. The conversation will still be based on evidence and facts, but you haven’t spent a zillion hours in useless, exhausting exercises, in this loop.

I am pro-competitive. I like competition. There is huge social value in good enforcement, so enforcers should also have more resources. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has 600 people in a country of 60 million: but DG Comp has less than 1000 people for half a billion citizens. That can change.

NS The new antitrust movement in US is perhaps about 10 years old, and extremely influential now. But there is no comparable movement in Europe to speak of? Why?

TV There is a bad and a good explanation. The bad explanation is that unfortunately it takes money to run alternative views. There is funding for this in the U.S., but in Europe there is less philanthropy, so there is a problem with organising.

The good reason is, perhaps, that concentration in Europe is not quite as bad as in the U.S. We have had more active regulators. We have made lots of mistakes, it’s been slow, it’s been late, maybe the remedies didn’t work out, but within the available laws Europe tried to achieve something. We ran three Google cases, we opened cases on Facebook, on Amazon. Especially in the first mandate of [European Commissioner for Competition Margrethe] Vestager, she had a mandate and the energy to do new things. The second mandate of Vestager hasn’t started with the same energy, I’d say.

In the U.S., after Microsoft in 1998 you had basically no enforcement for two decades in the Big Tech space. Now, at least, there is a change in climate in the US, with the Biden Administration. They are saying good words. Let’s see if the facts change.

Since leaving the European Commission, Valletti has returned to academia.

We welcome feedback on this and on other articles we’ve written.

Further reading:

I saw first-hand how US tech giants seduced the EU – and undermined democracy. Georg Riekeles, Jun 22

“Doubt is Their Product”: The Difference Between Research and Academic Lobbying – Tommaso Valletti, promarket.org

Increasing Market Power and Merger Control, Tommaso Valletti and Hans Zenger, 2019.

Scrambled Eggs and Paralyzed Policy: Breaking Up Consummated Mergers and Dominant Firms, John E. Kwoka, Jr. and Tommaso M. Valletti, Dec 2020

How to Tame the Tech Giants: Reverse the Burden of Proof in Merger Reviews - Tommaso Valletti, Promarket, June 2021

Endnotes

A short selection of articles, events and commentary.

Anti-monopoly: an open call for academic papers

The Anti-Monopoly Fund, established by Chris Hughes – an early co-founder of Facebook and now once of the company’s fiercest critics -- is providing academic research grants ($10K-$100K) to scholars interested in studying concentrated economic power and the evolving economy. (Since our Michelle is on the selection panel, we cannot submit anything but get in touch with Michelle if you’d like to find out more.)

Adaptive Antitrust

A paper presented by our co-founder Michelle Meagher to the the American Bar Association. It proposes a dynamic approach to antitrust adapted to the current context of extreme imbalances of power. It proposes an “excess power” standard to replace the dominant consumer welfare standard.

Global merger mania continues – Bain Capital.

From one of the leading cheerleaders of monopoly, Bain Capital, co-founded by former US Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney (see this 2012 Vanity Fair investigation of Romney and Bain by Balanced Economy co-founder Nicholas Shaxson.) The latest Bain report on global mergers and acquisitions says that “a lot of M&A got done last year, more than 28,500 deals . . . . . the superabundance of capital continued to drive high valuations.” It then asks, “will M&A activity accelerate out of this trough as the world recovers?” In a similar vein, the Financial Times writes that: Spac boom fuels strongest start for global mergers and acquisitions since 1980, reports on $1.3 trillion worth of deals in the three months to March 30, bringing more than $37 billion in fees to investment banks. “The deal activity is out of this world,” a UBS banker enthused. While the story is essentially a factual reporting of the numbers, it is suffused with unwarranted positivity. Here at the Counterbalance, we will seek to encourage journalists to leaven such reporting with commentary on the devastating human consequences: we hope that giant mergers come to have the same public taint as tax haven activity, arguably just as socially destructive.

Joint letter on protecting end users’ rights in the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) – Article 19

Over 30 civil society organisations have signed this open letter which criticises the European Commission’s proposal last December for focusing excessively on the relationships between core platforms and their business users, and on the economic aspects of relationships between competitors – while all but ignoring the interests of end users and citizens. The proposal leaves power concentrated in the hands of a few gatekeepers, rather than opening the market up to more competition, giving end users more choice between platforms. Instead, the DMA proposal leaves platforms with “too much power over users’ rights and over the flow of information in society.” The organisations note that the EU’s proposals for its Digital Services Act (covering digital services) and the DMA (covering digital markets) have been presented as separate complementary proposals: in reality, they should be considered holistically, together, to fill these crucial gaps. (We’d add that Tommaso Valletti’s big proposal could help overturn this gatekeeper power.)

America’s new corporate tax plan

In the last edition of The Counterbalance, we looked at how an unfair level playing field in a particular area of tax single-handedly wiped out a slew of small businesses in the U.K. The United States is now leading a welcome about-turn on corporate tax policy, which, among other things, has the potential to address corporate size.

This plan would help the U.S. and other countries: the UK could gain £13.5 billion a year, on one estimate. In a forthcoming edition of The Counterbalance we will delve into the peculiar relationships between the similar-sounding but very different arenas of market competition, the “competitiveness” of countries (or of tax or regulatory systems,) and competition policy.

Tell Biden: No Section 230 in Trade Deals

A letter from American Economic Liberties Project, a U.S. antimonopoly group, urging the Biden administration to stop the Trump-era practice of inserting into trade deals language letting tech firms evade domestic liability for violating civil rights laws. Big tech platforms are pushing to use “trade negotiations” to limit the domestic policy space available to U.S. Congress, regulators and courts to address privacy concerns, civil rights, monopoly, and other matters. There has been a deep well of activism over global trade for many years: new antitrust thinking has the potential to create powerful new tools and alliances. We will return to this theme repeatedly in the years to come.

Children’s social care market study: Invitation to comment.

The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) launched this Invitation to Comment on why the UK’s “market” for children’s social care seems to be so dysfunctional. Among other things, they asked for comment on the role of the role of private equity (PE). Our submission to the enquiry focused on some of the extractive techniques pioneered and used in PE, which have spread far beyond the sector. The core technique has generally been to buy a company, force it to borrow excessive amounts, take a large slice of the proceeds for the owners/investors instead of investing it in the company, then leave the company and its various stakeholders on the hook for the debts. The General Partners that run the PE firms thus take large rewards while transferring the risks and costs onto others’ shoulders: a recipe for recklessness – and for being able to out-compete other less predatory firms in the market for acquisitions, creating a contagion effect. Our forensic submission found strong evidence of this in the children’s social care sector in the UK, with PE firms performing far worse than non-PE firms on a range of metrics. Our submission went beyond many previous analyses of the financialisation of care by showing how these skewed incentives distorted the market in harmful ways. We will look at this in more detail in future editions of The Counterbalance.

The Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF)

This month the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority joined the DRCF as a full member to this forum, which includes the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and the Office of Communications (Ofcom.) Co-operation in these areas is, in principle, a great idea. Will it be constructive? We urge that such bodies are democratised and made more transparent, opening up to allow the participation of voices from outside the usual competition bubble: small businesses, trade unions, NGOs, and more.

CMA clears Uber and Autocab deal

Why is Uber buying booking and dispatch technology software (BDT) for taxi companies? That’s a possible choke point falling straight into Uber’s hands. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) said that “Autocab and Uber could try to put Autocab’s taxi company customers that compete against Uber at a disadvantage by reducing the quality of the BDT software sold to them, or by forcing them to pass on data to Uber” but concluded that “The CMA has found no competition concerns as a result of this deal” since, they argue, taxi companies could just switch to other BDT suppliers if they didn’t like it. That is asking the wrong question. The right question is: does this purchase, along with other acquisitions, increase Uber’s already market-bending platform power to crush taxi firms? Of course it does. Tommaso Valletti’s big recommendation could have certainly helped, in this case. There’s a campaign to be had here, of course.

Coming soon: a reading list of new antitrust books and articles.