The Scott Morton affair: anatomy of a democratic victory

Democratic pushback helped overturn a deeply troubling appointment

Welcome to The Counterbalance, the newsletter of the Balanced Economy Project. This edition looks at the recent appointment of Fiona Scott Morton as Europe’s Chief Competition Economist, and her subsequent withdrawal in the face of a political firestorm. Our endnotes provide more good news, as we discern the beginnings of a global sea change in how regulators tackle excessive concentrations of corporate power.

It was about half way through the European parliamentary hearing on July 18 when this classic European stitch-up began to unravel beyond repair, and when democracy began to re-assert itself.

The subject was Fiona Scott Morton, a high-profile U.S. economics professor whom the European Commission had announced a week earlier would be its next Chief Competition Economist.

A huge political backlash had already built up against her appointment. In France, a train of political actors — including, eventually, President Macron — railed against the appointment and urged the European Commission to re-consider. The French mostly focused on her American nationality, amid oft-repeated stories about the "vassalisation" of Europe by the United States.

Defending her, a group of 39 prominent economists from many countries weighed in, calling her "one of the best" economists in the field, and urging the EU to recruit the best, "independently of their nationality."

This focus on her passport helped the Commission, led by Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager, stick to their guns - for this was a welcome distraction from the real trouble with Prof. Scott Morton.

For a first flavour of this trouble, see this headline from 2020:

The risk was not, as many in France had previously argued, of Europe being "owned" by the United States -- after all, many top US antitrust officials these days loathe Prof. Scott Morton's views. No, the true risk is that Europe is 'owned' by Big Tech and big business. A letter we co-published in May spelled this out in a European context:

We’ll get to these strange arguments in a second: but for now, note that our letter then generated a new issue. The Financial Times, reporting on it, cited "a person close to Scott Morton" as saying "the consulting work she has done for Big Tech ended two years ago and there may not be conflicts of interest.” Two years? As we had already noted, she authored a consultancy document that Microsoft had published, dated less than five months earlier.

Commission officials had sought to address the issues by saying Prof. Scott Morton would recuse herself from cases where she had a conflict. But this raised more questions: how would they cope with some of their most high-profile cases, or strategic discussions about markets, if she had to absent herself? Amazon, Apple and Microsoft bleed into so much. It made no sense.

The car crash hearing

Vestager's performance at that July 18thhearing, at the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, was pretty disastrous.

Their assessments of Prof. Scott Morton’s conflicts of interest was "ongoing", she said, and that in any case involved only a "handful of cases or less." But the list of those conflicts was unfortunately "confidential."

Portuguese MEP José Gusmão responded, and the gloves came off.

"You say [the list of her conflicts] is confidential. Well, I think this is scandalous," he said. "We cannot scrutinise conflicts of interest when the Commission themself is hiding indispensible information . . . if it is a handful of cases, please share with us: which cases are involved? Which companies can Prof. Scott Morton not work on?"

Vestager's answers were stunning.

"The detailed assessment is ongoing, so even if I had wanted to I could not give you this list today," she began, adding that “this is handled the way we have handled things before. Previous Chief Competition Economists have been doing consultancy work: it is quite common in the academic world.”

"This has been handled before without anyone asking for us to disclose what arrangements were made for conflict of interest."

So . . . that's OK then! It’s secret, and that’s how it’s always been done! And she followed that, with this:

"That makes me a bit worried that it boils down to the passport."

There was some light heckling at this transparent attempt at distraction. Gusmão responded icily:

"As you should have noticed from my question, I did not refer to [her] citizenship. . . that does not interest me one bit," he said. “My question is about revolving doors.”

MEP Aurore Lalucq then ramped up the pressure:

"I think the problem we have have here is one of trust. We are asking you specific questions here, and you are not really answering: you are talking down to us. We need respect as Parliamentarians. And I think we here are all unanimous, and that is pretty rare for the parliament.

“You have said the list is confidential. But we want the list."

Vestager had nowhere left to go. "Professor Scott Morton is not a lobbyist," she floundered. "She has not been a lobbyist. She has been doing some consultancy work."

Garbage in, garbage out

When people call Prof. Scott Morton "the best" or "one of the best" industrial economists in the world - what does this word 'best' mean, amid this mess and murk?

And the conflicts of interest were merely the first problem with this appointment. There's another, perhaps equally serious.

MEP Paul Tang asked why the Commission seemed so keen to pick Prof. Scott Morton. Was it, he wondered, because of her role as a world-leading proponent of the (outdated, pro-monopoly) "Consumer Welfare" ideology?

Plenty has been written about this laissez-faire theory, which first became prominent under U.S. President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, then in Europe and beyond. The basic idea here is that regulators should ignore messy things like the interests of citizens, workers, taxpayers, democracy, the environment, the broader public interest — or power — and instead narrow the field down to two things that economists can measure: prices for consumers, and output (or “efficiencies,” as they call it).

Under the crudest version of Consumer Welfare, it's perfectly fine to allow giant firms to smash unions and crush workers, let industries pollute, let tech firms steal our data and use them to manipulate us, under an assumption that these activities will generate a corporate surplus (or "efficiencies") that should trickle down to consumers.

In practice, of course, the defenders of this philosophy are more sophisticated than this (as you can see from Prof. Scott Morton's own writings on the topic.) But 'sophisticated' may put it kindly: through this frame economists wield complex models rooted in other-worldly assumptions, to deliver Alice-in-Wonderland results that justify mergers, bigness and dominance.

Take, for instance, an article by Prof. Scott Morton in The Washington Post entitled Why 'breaking up' Big Tech probably won't work (where, by the way, we find no disclosure of her conflicts). Or see the above-mentioned document she authored for Microsoft last December, pushing for the company to be allowed to merge with gaming firm Activision Blizzard.

That merger, she wrote, "does not pose a competitive harm and, in contrast, is likely to promote competition in a variety of markets."

Wait a moment, though.

* * Two giant firms become one super-giant firm ==>> more competition. * *

How does that work?

The basic idea here - and we see this argument all the time - is that when elephants (or elephantine firms) fight —in this case, Prof. Scott Morton was pitting Sony against rival gaming powerhouse Activision — you make the contest fairer by making the weaker player stronger - in this case, vastly stronger.

The problem here is that when giants fight, it’s the grass, the smaller creatures, that get trampled. We believe a better general way to make the contest fairer is to tame, shrink or corral the big elephants and, where possible, make space for the smaller creatures to graze - and flourish. Re-balance the economy.

But under this dominant, giant-focused world view, regulators find it hard to see the collateral damage from excessive power. So it has been a passport to mergers, bigness and market power.

Of over 8,800 mergers notified to the European Commission since 1990, only 32 have been prohibited: less than 0.4 percent. (And that's only the big mergers that get notified: the true ratio is starker.)

Even on its own narrow terms, Consumer Welfare has failed.

Look at "markups" - roughly, the ratio of prices versus costs of production, since the Chicago-School revolution.

The markups have hurt consumers, and the ensuing profits from markups have trickled up to shareholders - because those firms have the power to stiff consumers too.

Is this why, as Tang's question suggested, this appointment was pushed through against such opposition? Different sources told us as early as May how badly they seemed to want her: that the appointment had essentially been decided far in advance, and there was reportedly "no discussion internally" ahead of the announcement. They even, as we noted in May, bent their recruitment rules, apparently to get her in.

And here, we should mention one more instance of odd manoeuvring behind the scenes.

Box: A Double coincidence?

We had contact with a Brussels lobbyist who had received an official email from Helena Malikova, an enforcer in the EC's Chief Competition Economist's team (she had led the investigations into several tax planning cases reviewed under State Aid rules, notably the multi-billion dollar Apple case.) In her email, which was about her speaking at an upcoming event, she said she had been told on July 11th, the same day that Prof. Scott Morton's appointment as Chief Economist was announced, that she was being removed from the Chief Economist's team - and that she would have to move on September 1st, the same day Prof. Scott Morton would have taken up the post. The lobbyist called this a "double coincidence" and added:

"I find the timing of these decisions to be a worrying sign. Helena has over the past few years expressed concerns about conflicts of interest among economists who consult for companies."

We also recently flagged a paper co-authored by Ms. Malikova, entitled "Spamming the Regulator," describing how economic consultancies had produced a "strategic oversupply of submissions and economic arguments" that overwhelm regulators' capacity, rather like those distributed denial of services (DDoS) attacks that bring down web service providers on the internet.

The paper also criticised the role of anonymous academic experts, who appeared in submissions with titles such as "Professor A." This anonymisation enables conflicts of interest, for example if a Professor advises the Commission how to design regulatory rules - then advises private companies how to get around those same rules. This has doubtless earned Ms. Malikova no friends among the powerful economic consultancies whose members shunt back and forth between key European posts, in a merry-go-round of revolving doors.

The dam breaks

The morning after the July 18th hearing, this happened:

(No mention of the conflicts, but still.)

We understand that our letter, which re-circulated widely ahead of the hearing, was a significant factor in breaking the logjam, by helping or enabling the debate to shift decisively away from nationality, towards the conflicts of interest. This was a stronger foundation that allowed many more groups, from many more countries, to join in.

This climb-down is a significant victory for democratic forces, and we're proud to have, with our allies and our network, played a part.

Now, what comes next?

Reclaiming European market regulation

The European Commission will, it seems, re-open the selection procedure for this crucial post in September.

Will the successful candidate be better, or worse? Someone who sees and confronts power? Or someone who avoids looking at the elephant in the conference room?

Well, there are grounds for both pessimism, and optimism.

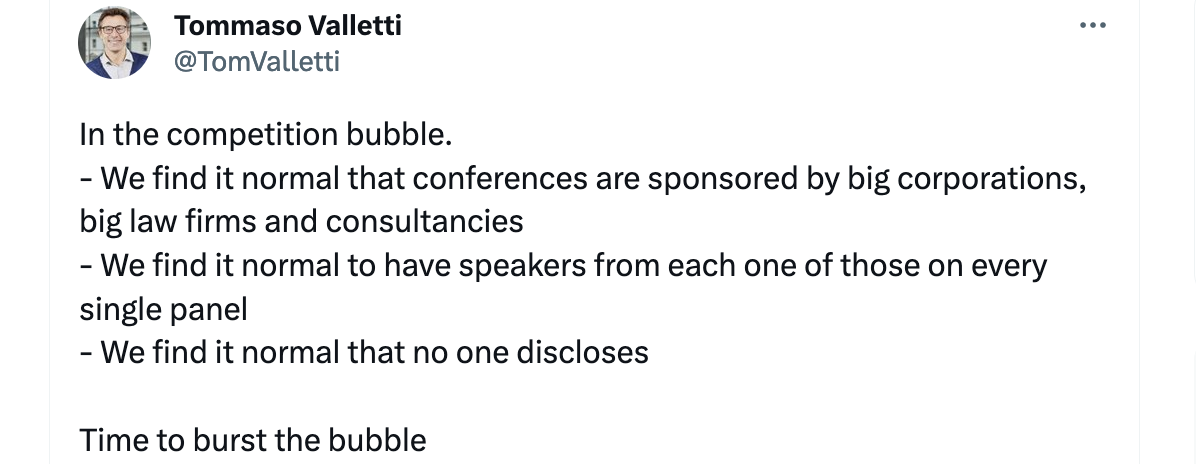

For the pessimists, see our interview with Tommaso Valletti, a former EU Chief Competition Economist (the same role Prof. Scott Morton would have had,) laying out the extensive conflicts of interest and bad faith, across the system. He leveled particular ire at consultancies representing big business, including Compass Lexecon, Charles River Associates (CRA,) and RBB.

"I saw the consultants hijack a certain way of doing economic work. They do this on a massive scale, to create doubt. They bombard you. They say ‘well, this merger could bring all these fantastic efficiencies: here is a possibility you should consider.’ You know that in practice this will not play a role, but then you have the burden of proof as an authority to dismiss those claims. It is a very dirty game."

The consultants get paid a lot for this smoke-and-mirrors. A lot. Valletti continued:

It made me re-think my own values. This is not about some narrow economics. It’s about democracy, about economic and political power."

Just as tax haven lobbies have been found out bragging of enjoying "superb penetration" at the apex of the British government, the consultancies enjoy similar in the EU, even boasting about it on earnings calls.

The cynical view here would be that the system is irredeemably rotten, and we can't do much to fix it.

But there's another, more hopeful view. Valletti once got the job, as did his (we believe unconflicted) predecessor Massimo Motta - thus showing that it is quite possible for perfectly good independent people to get appointed.

The July 18th hearing is another sign that European democracy, while certainly battered, is far from dead. Given the latest furore, we'd be pretty surprised if they selected a candidate with such conflicts again - and we wonder how many conflicted candidates would now think it is even worth applying.

More likely, would be another candidate steeped in the Consumer Welfare world view. Even then, though, a candidate without (or with fewer) conflicts would likely be far more open-minded to the rising dangers from corporate consolidation.

A global sea change: will Europe keep up?

There is another reason for optimism: a worldwide anti-monopoly sea change now starting to get traction — a change that is very significantly the fruit of a radical insurgent civil society movement, which first emerged in the United States a bit over 10 years ago, and gained proper traction in the Biden administration in mid-2021.

The EU has certainly made some strides forwards, notably with its recent Digital Markets Act. But we're seeing leading enforcement agencies, politicians, and civil society around the world, in Germany, France, the UK, Australia, and the United States, rapidly starting to move further, faster than the EU, towards a new consensus about how to tackle the snowballing threats from dominant tech and other firms. (Our endnotes below give a flavour of latest signs of this sea change.)

Europe is falling behind the curve. Who it chooses for this crucial post will signal whether or not it plans to catch up, and roll back the stranglehold that monopolists increasingly exert upon our vulnerable economies and societies.

Endnotes

We may be, we hope we are, at the start of a global revolution in tackling excess corporate power, and we’ll do what we can to encourage it. We see a steady drumbeat of progress that amounts to far more than just tinkering. For example, a recent ruling by EU courts to allow competition regulators to take privacy issues into account - two previously siloed areas - is “huge.” And, as mentioned in our previous newsletter, the UK has a hard-hitting new Competition Bill, and its Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) took the courageous step of blocking the Microsoft-Activision merger (it recently had to perform a partial climb-down in the teeth of legal, lobbying and political pushback, but it is still expected to wring major concessions from the giants).

Here are a couple more signs of the sea change:

Radical new US merger guidelines

New draft U.S. merger guidelines have provoked hyperventilating criticism from big firms and their supporters. The draft guidelines represent, as one European competition expert put it, "the biggest shift in US antitrust policy in decades." The changes have several powerful elements: we’d highlight first a flipping of the burden of evidence for large mergers: from the current presumption that a merger is good (so that regulators have to climb a mountain to prove that it isn’t), to a situation corporations must prove that the merger will bring benefits. That’s huge.

The antitrust establishment has reacted with fury, but also with “Economics Imperialism” - the Chicago-School idea that economic analysis must trump the law. Carl Shapiro, a prominent U.S. antitrust professor (also linked to Charles River Associates) suggested courts may simply not follow the new guidelines. “They've been demoted from this articulation of economic principles, consistent with the case law, into a legal brief,” he sniffed. Piranhas will attack this draft: let’s see how far they get. (And, from Matt Stoller: “While Wall Street likes to act like the FTC keeps losing, it’s not actually true. The FTC has won 12 cases and lost 2, and settled 15. And the behavior of merging firms reflects that dynamic.”)

All change in Germany

Germany’s competition policy and enforcement has been feisty of late. In July they announced sweeping reforms to their Competition Act (GWB,) which State Secretary Sven Giegold described as "the most fundamental since the legendary minister for economy Ludwig Erhard" - that is, in six decades. They will be able to impose remedies without having to undergo bureaucratic and difficult processes to prove abuse of a dominant position; they can more easily order the “unbundling” breakup) of problem companies; they can more easily remove “illegitimate super profits,” and it will become a lot easier to stop dangerous mergers. Dramatic stuff.

News from our network

The last edition of The Counterbalance contained bumper crop of news from our network; we have some brief network updates since then:

Call for Papers: Digital Markets Act

The Amsterdam Centre for European Law and Governance, the Hertie School Centre for Digital Governance, the University of Trento, and free speech organization ARTICLE 19, are organising a call for papers and a two-day symposium, to stimulate research and debate on the Digital Markets Act (DMA), especially on crucial themes that have been overlooked.

Templates for gatekeeper compliance

Some of us came together to urge the European Commission to sharpen its template for “gatekeeper” platforms to comply with the DMA. With sloppy drafting, the giants will run rings around the enforcers.

Irish regulator in court over massive Google data breach

Not strictly a network activity, but still. On Thursday, 27 July, the Irish High Court will hear a case taken by our allies at the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) against the Data Protection Commission (DPC). ICCL alleges that the DPC has failed to protect people against the biggest data breach ever recorded: Google’s “Real-Time Bidding” online advertising system. (See also Ireland's privacy regulator is a gamekeeper-turned-poacher, Cory Doctorow.)

EC to investigate Amazon-iRobot

On 6 July, the European Commission announced an in-depth investigation into Amazon’s plans to buy home robotics company, iRobot. This follows concerns raised by SOMO, Foxglove, the Balanced Economy Project and the Open Markets Institute in February to investigate the deal, as it would put new Amazon eyes inside our homes and, yet again, entrench its market dominance.

Pushback against Canadian bank merger

Our allies at the Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project have asked the Department of Finance not to allow the banks RBC and HSBC Canada to merge.