To tackle corruption, start with monopoly power

It is not only public officials who abuse power for private gain

Welcome to The Counterbalance, the newsletter of the Balanced Economy Project. This article has been updated from the original, with a brief section of additional analysis.

A few years ago I arrived at Luanda airport in Angola to do research into oil money and capital flight out of Africa into rich-country tax havens. At immigration they told me my vaccinations were out of date, and shepherded me into a small room where I was given two options: either be injected with a scary-looking needle lying in a metal tray nearby, or be packed onto the next plane back to Johannesburg.

We all knew there was a third, unspoken option. Pay a bribe.

Thankfully, I was in no hurry: by staying calm, and by presenting a quiet contrast to a sweaty Portuguese fellow traveller yelling about corruption, I was able to front it out and eventually exit without paying a bribe. But I do remember my overwhelming emotion at the time: fear.

Those airport officials were gatekeepers, with power to block my entry into Angola. They were abusing their power to try and extract a private payment: a classic corruption scheme.

The idea that corruption is the abuse of power for selfish gain goes at least back to Plato, who associated it with tyranny. This idea has endured through the ages: Transparency International defines corruption as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.”

If ‘abuse of power for private gain’ has got you thinking about concentrated econoimc power, you’re right on the money.

Plato was thinking about political rulers, and most people understand that autocratic states tend to be more corrupt than genuinely democratic ones.

But the very same principle can apply in the economic domain, where dominant actors can enjoy immense gatekeeper power. Indeed, antitrust (or competition policy) rules such as the European Union’s Digital Markets Act now deem dominant firms as ‘gatekeepers,’ and subject them to special rules to tackle what they call abuses, but what you might also call corruption.

Once we understand how closely monopoly power — sustained, durable concentrated market power — is linked to corruption, this opens up immensely powerful but largely forgotten toolkits, to tackle both scourges.

Bigger, richer, more corrupt

The first link between anti-corruption and anti-monopoly is pretty obvious. Like heavily weighted dice, the more money a company has, the more it can corrupt. And monopolists tilt the playing field, to get richer than the rest.

Consider, first, a non-monopolist company operating in a strongly competitive market. The fiercer the competition, the more it must invest any profits back into the business, to stay ahead of rivals. Any economic surplus is likely be, as economists put it, ‘competed away’ to the minimum needed to stay afloat. So it is will have little spare cash for lobbying. Not only that, but sector-specific lobbying is unlikely to help much, because any extra profits it can reap from lobbying are likely to be, again, ‘competed away,’ leaving it back where it started.

But a monopolist like Amazon or Pfizer is in a different position. For one thing, monopolists tend to be vastly more profitable than firms in highly competitive markets.

If they have entrenched market power to trap potential rivals in their gravitational force field, they need not worry so much about investing to stay ahead of those rivals. This frees up surplus funds for other ends – like spraying money around think tanks, universities, advertisers, and political campaigns, to further their private goals (often to entrench or boost their powers yet further.)

As former European Commission official George Riekeles described what it looked like from the inside:

“well-organised citizens’ and stakeholder groups came to put their views as well as canvassing members of the European parliament. At one point, I remember thinking: who are these people?”

A report by LobbyControl and Corporate Europe Observatory gives a flavour.

Liza Lovdahl Gormsen, a lawyer who launched a class action suit against Facebook/Meta in the U.K, explained how hard it was to get any good economists to help her, because Meta had instructed almost all the consultancies. “So they are conflicted,” she said. “It was next to impossible to get anybody to help.”

So that is the first point: in terms of greasing the wheels of politics with lobbying, bribery, sponsoring think tanks, academics, and so on — all activities that may be legal but still carry a whiff of corruption — monopolists have both more ability, and more incentive, to be corrupt. And a track record too.

Mergers as Shakespearean drama

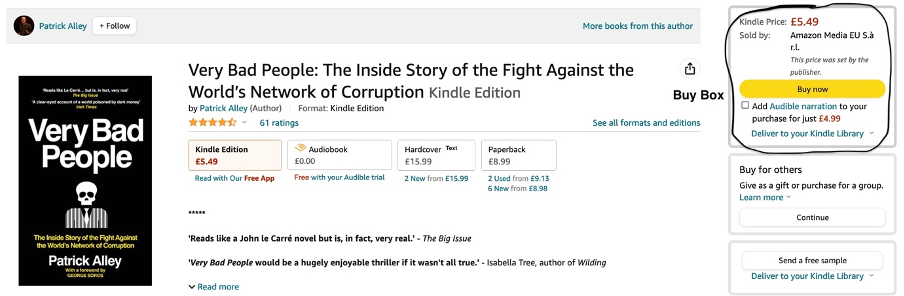

Consider Amazon’s “Buy Box,” shown in the picture below. Amazon’s promotional materials have said that “90%+ of sales” go through the Buy Box - so many businesses know that Amazon can destroy their business overnight with the twitch of an algorithm, or the arbitrary pull of hidden levers - with no recourse.

That makes the Buy Box an awesome instrument of power over sellers on its platform.

The counterpart of this gatekeeper power is fear: fear of speaking out, of upsetting the monopolist. That’s why so many small businesses stifled in Amazon’s embrace take their medicine and pay their fees (that can add up to half of their revenues) so silently.

Academics call this power-based extraction rent-seeking – a term widely associated with corruption.

Or consider the football governing body FIFA, the global monopoly provider and allocator of lucrative World Cups. Is it such a surprise that it is so beset by corruption scandals?

Amazon, Google with its dominant search rankings, FIFA, and those officials at Luanda airport, are all gatekeepers controlling who gets to where they want to go, whether it is into the Buy Box, into the top search ranking amid a heated political contest, to host a World Cup, or to get into Angola.

I rightly saw those airport officals as behaving corruptly – so what’s different about Amazon or Google or FIFA, if they abuse their power to shake down those under their thumb? Whether their power is public or private, it’s the same tyrannical problem. As the anti-corruption scholar Zephyr Teachout notes:

“When you see power that can control, set terms, direct – that is governing power: whether you call it the mayor, or the CEO.”

Source: Zephyr Teachout speaking at the Re-Balancing Power anti-monopoly conference in Berlin last year. The video is well worth watching.

She adds that we have seen over half a million corporate mergers globally in the past decade or so:

“And once you start to see a merger, the way that Shakespeare might see a merger between families as a political moment, not an economic moment, you can see the scope of this political revolution”.

And remember: society entrusts dominant corporations with governing power through deliberate policy decisions to let them grow so powerful. Now read that corruption definition again: “The abuse of entrusted power for private gain”.

If we have built corporations to be self-interested, then granted them extensive governing power, we will have built ourselves a system of corruption. We could easily reduce their power, and thus the corruption, with enlightened legislation.

Waiting in line

There are other ways to think about corruption. The Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe touched on an important aspect: how corruption becomes systemic:

“A normal sensible person will wait for his turn if he is sure that the shares will go round; if not, he might start a scramble.”

My favourite author continued:

But the more damaging way to disrupt a queue is to push in at the front. This assaults everyone’s belief in it, and if a scramble begins, it will collapse. The firehose disrupts the queue. Pushing in at the front corrupts it: there is then no easy way to rebuild it. Believing that your colleagues will loot the hospital budget may make you more inclined to loot it first, because the medicines will disappear either way. Again, we can go back to Plato, and “the corruption of the citizenry.”

What has this more systemic approach to corruption got to do with monopoly? Well, consider the ‘winner’ of a Google search result, or the company that gets into Amazon’s Buy Box. They got to the front of a queue. Those giant firms have picked the winners – on the basis of opaque algorithms or other often arbitrary criteria: ones that maximise their profits, rather than serve a broader public purpose.

If, by contrast, those firms instead had a tiny market share each, they would lose that power to decide who lives or dies. As a landmark U.S. Senate report, the “Ciciline report,” put it:

“because the dominant platform was, in most instances, the only viable path to market, its discriminatory treatment had the effect of picking winners and losers.”

So monopoly power automatically fosters discrimination: it is baked into the system. And there’s nothing like discrimination to damage – or corrupt - everyone’s faith in the system, and thus the system itself.

Not just corrupting, but corrupt

You can look at all this a different way, again.

Consider a cartel between five firms, to rig a market for widgets. Many countries have laws against cartels, for good reason: they are, as Cory Doctorow notes, “real conspiracies” to corrupt markets.

But now what if the firms change strategy and instead of running a cartel, they decide to merge into a single dominant firm, to create, in effect, a reinforced, legalised version of that cartel. Their cartel-like activities may be legal now - but has the merger changed the underlying nature of that market corruption? No: it may well have strengthened it.

It used to be widely understood that dominant corporations were not just corrupting – in the ways they interact with others – but that in their dominance they themselves could be inherently corrupt.

But this idea has fallen out of favour, as part of an intellectual revolution from the 1970s that demonised government and elevated markets as the arbiter of what is good and bad.

Under this anti-state, anti-tax, anti-regulation movement corruption became associated only with formal elected political office, and economic dimensions of corruption fell out of view (hence the World Bank’s narrow definition of corruption as “the abuse of public office for private gain”.)

As part of this same revolution, antitrust or competition policy narrowed its focus down to consumer welfare and measurable economic efficiency, and lost sight of power. As Tommaso Valletti, a former Chief Economist at the European Commission, added:

“I do take the view that big is bad, because concentration is political power, it is corruption, it is a risk to democracy. We have lost this idea, and instead the economists are enamoured with “efficiency.”

The economists cannot see corruption - and the problem is more generalised, as Teachout underlines:

“Antitrust can’t see political power, and the anti-corruption can’t see economic power.

I have experienced this as an academic I go to antitrust conferences and say there is a real political problem. They will pat me on the shoulder and say ‘that’s right: there is a very significant problem with corporate power in politics! And it is not our problem: the anti-corruption people do that.’ ”

There are provisos to consider. What about, say, a trade union which builds and wields collective power, with some similarities to a monopolist, or a cartel? Is that corrupt?

The answer here is that the corruption definition contains three components: abuse, power, and narrow selfish interest, and ALL three need to be in play. So a trade union would escape being called corrupt on two of those three criteria: trade unions represent workers as victims not perpetrators of power, so building collective power to protect workers is not an abuse; second, trade unions represent large numbers of people, some numbering in the tens of millions. That is far from a narrow selfish interest.

It is possible and indeed it has happened that trade union bosses might wield power abusively in their own selfish interest (you might watch Martin Scorsese’s 2019 docu-drama The Irishman to get some real-world examples;) in such situations all three criteria would be present and we would reasonably think of this as corruption in any case.

The powerful but forgotten anti-corruption toolkit

Corruption scandals inspire widespread public condemnation, send people to jail, and topple governments. It is quite possible now to start re-directing this anger and action in the direction of monopoly power or excessive concentrations of economic power.

Whatever we try to do, whatever the goal – whether it is to accelerate the energy transition, tackle inequality, foster economic resilience, improve productivity, curb fake news, or . . . tackle corruption, we are hemmed in by concentrated corporate power, monopoly power. Giant energy firms, too-big-to-fail banks, Big Tech firms, the Big Four audit firms, Big Pharma, and so on: they block change.

We’ve said it before: if we focus only on these firms’ behaviour and activities, but leave their power intact, we will continue to snap at the heels of giants, operating within the tight bounds of their gravitational force fields. It's no different with anti-corruption work. If you try to stop powerful corporations from using power corruptly, without addressing the roots of that power, we won’t get very far.

The good news here is that there is a fearsome but forgotten legal and regulatory toolkit – the Americans call it antitrust, and we call it ‘competition policy’ – which governments can and do use to take down monopoly power (and with it, economic corruption.) This toolkit can potentially break up giant firms, stop them merging to acquire more power, stop them using their arbitrary power to discriminate, and bind them with powerful rules and enforcement teeth that most other government agencies can’t begin to match.

The current problem with this toolkit is that in Europe and in many other parts of the world it has been heavily captured by big money, so it has become rather ineffective , even pro-monopoly. And as a result, most people ignore it.

But this is just now, starting to shift. Antitrust authorities worldwide, spooked in particular by the dangers of big tech and AI, are belatedly starting to get more serious, ranging from new efforts to break up Google in the United States (and much more besides,) to the UK’s recent laudable move to stop Microsoft buying the gaming company Activision, to the EU’s Digital Markets Act. None are perfect, but if we can encourage progress here, the results could be genuinely transformative.

These anti-corruption tools have serious teeth — far more than what any anti-corruption agency has — and yet how many anti-corruption activists pay attention to antitrust, let alone tried to sharpen it?

Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. To de-corrupt our economies, start by de-monopolising them. And this will tackle a host of other problems, along the way.