Who owns the stage? A look at music industry monopolies: part two

Hello and welcome to the latest edition of The Counterbalance. This week, we’re continuing our work on monopoly power in the music sector.

In last week’s edition of The Counterbalance, we outlined how monopoly power in the music industry — dominated by a few record labels and streaming giants — has distorted markets in the sector.

This week, we dive deeper into the challenges faced by independent artists and smaller creators that are tasked with navigating an ecosystem that is increasingly closed off by a handful of corporate giants.

For many independent musicians, the reality is clear: despite streaming technology’s promise of democratising music distribution, gaining visibility is an uphill battle.

With the major labels — Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group — controlling roughly three quarters of the globally recorded music market, artists that don’t fall under their collective banner are pushed to the margins. Streaming giants like YouTube, Spotify and Apple compound these challenges with algorithms that prioritize mainstream hits and reduce opportunities for independent voices.

Maverick Sabre, the Irish-English artist known for speaking out against the status quo in the music industry, captured the frustration when he announced he would re-record his debut album independently:

“Today marks the start of gaining back control and ownership over that part of my catalogue. I have never received any royalties from that album, a story that is not uncommon in the music industry,” Sabre said in a post on X. “I want to change the narrative on artists and the industry, help me do this,” he added.

Sabre’s experience isn’t isolated, either. In this article in The Standard, famed British artist Raye lamented a period in her career where she struggled professionally — and personally — under a former producer.

“I was a product,” Raye told Louis Theroux during an interview. “When you take a step back and remove emotion, I was a product that needed to be sold.”

Indeed, monopoly power in the music industry doesn’t just squeeze artists economically, it reshapes and dampens the creative freedom and diversity upon which music itself depends.

Small creators have not stayed silent, however. In this New Statesman article, British artist Tom Gray — a member of the Performing Rights Society — discussed a new campaign he launched in 2021 called Broken Record, calling for change to the music industry.

“There is a cultural delusion around the glamour of music which is for the most part portrayed and pushed by musicians themselves, in order to maintain the appearance of success,” Gray said, adding “but even very successful musicians and artists that you’ve heard of do not make enough money from recorded music to pay their rent.”

The power imbalance also impacts how new technologies, particularly AI, are being integrated into the music sector. As we learned in last week’s edition of The Counterbalance, major labels and streaming services hold significant control over how content reaches audiences.

Smaller artists — particularly those seeking to represent minority cultures — are now facing the very real risk of losing control over their creative output entirely.

According to a 2024 study out of The Netherlands — which studied Turkish-origin users and Dutch users — platforms like Spotify had a “generic popularity bias”, exposing the need to “improve the representation of users with non-mainstream music preferences.”

The study, authored by Shah Noor Khan, Eelco Herder and Diba Kaya, found that this problem is not exclusive to Turkish-origin and Dutch communities, but is instead indicative of a wider issue of “popularity bias and the recurrent recommendation of popular songs, keeping users in a repetitive loop that hinders the exploration of new music.”

These problems worsen when one considers the inclusion of AI in music generation, a technology that the world’s tech streaming giants already exert dominant control over.

According to Atharva Mehta, Shivam Chauhan and Monojit Choudhury, an analysis of over one million hours of audio datasets used in AI music generation research identified a “critical gap in the fair representation and inclusion of the musical genres of the Global South.”

Their study, titled “Missing Melodies: AI Music Generation and its ‘Nearly’ Complete Omission of the Global South” found that musical genres from the Global South accounted for less than 15% of the musical datasets reviewed for the study.

In next week’s edition, we will examine practical solutions and policy reforms that are required in order to dismantle the stranglehold that unchecked corporate power currently enjoys over the music industry.

Weekly highlights:

One to watch: Mexico’s competition watchdog, the Federal Economic Competition Commission (Cofece) is expected to rule on whether Google built an illegal monopoly in the world of digital advertising in the country. According to public documents, the decision could result in a fine that costs Google 8% of its annual Mexican revenue.

A look at monopoly power in agriculture: US District Judge Iain Johnston issued a blow to agriculture giant Deere this week, when he ruled to reject the company’s efforts to end a lawsuit filed by the Federal Trade Commission in January. The lawsuit accuses Deere of forcing farmers to use its authorised dealer network and driving up repair costs.

Soundbite of the week: Europe, Big Tech and a contest about fees

Tech giants meta and TikTok have lashed out against a supervisory fee levied by the European Commission, labelling the fee as disproportionate and based on flawed calculations earlier this week.

Under the Digital Services Act, Meta and TikTok are two of 18 companies that are required to pay a supervisory fee amounting to 0.05% of their annual worldwide net income. The fee is used to cover the European Commission’s cost of monitoring compliance.

Meta’s lawyer Assimakis Komninos hit out at the methodology behind the fee, stating that the company did not know how it was calculated, and that the provisions “go against the letter and the spirit of the law.”

Bill Batchelor, representing TikTok, said “what has happened here is anything but fair or proportionate. The fee has used inaccurate figures and discriminatory methods.”

For what it’s worth, the Commission’s lawyer, Lorna Armati, brushed these criticisms aside, and defended the Commission’s use of group profit to calculate the fee:

“When a group has consolidated accounts, it is the financial resources of the group as a whole that are available to that provider in order to bear the burden of the fee.”

Data mining: A look at private equity and healthcare

Loyal subscribers to The Counterbalance will remember a recent edition of this newsletter which looked at the immense harm and damage that private equity can cause in the healthcare industry.

According to a study cited in that edition, private equity-owned US nursing homes dealt with an 11% increase in mortality rates due to a decline in key metrics, including nurse staffing.

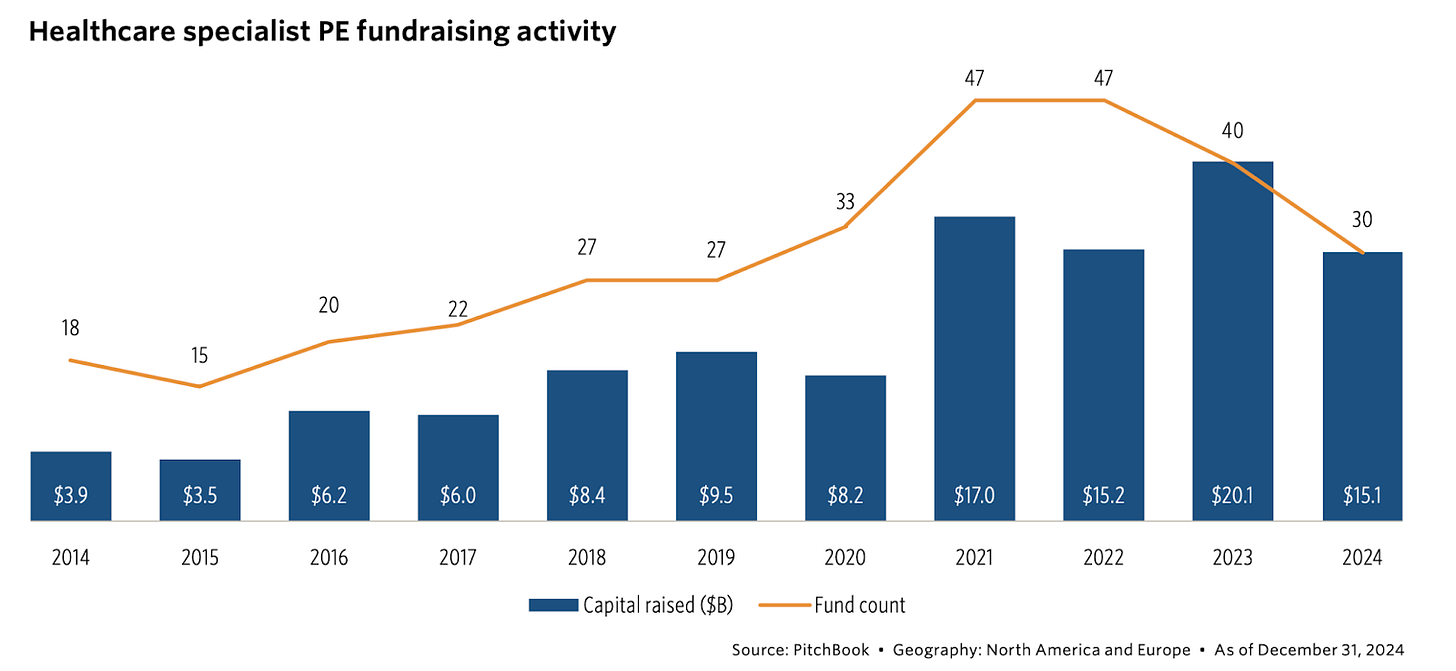

When the stakes are that high, it’s important to keep a consistent eye on the influx of private equity into the healthcare sector. According to recent data shared by PitchBook, healthcare specialist private equity fundraising activity faced a downturn at the end of last year, culminating in just over $15 billion, a significant drop off from 2023’ figures of over $20 billion.

The Counterbalance is published every Thursday. Please send any thoughts and feedback to scott@balancedeconomy.org.