Welcome to The Counterbalance, the newsletter of the Balanced Economy Project. Today’s article is a precursor to a report we’ll be publishing soon about the need to break up dominant firms: the whys, the whens (and the when nots), and the hows of breakups. This article asks a focused question: can breakups be used to tackle toxic online content?

A couple of weeks ago Frank McCourt, a wealthy entrepreneur and "social impact" investor who has been critical of Big Tech, launched a "People's Bid" to buy Tiktok and to re-engineer the platform "to put people in control of their digital identities and data." Tiktok's Chinese links has put it in US officials’ crosshairs, and last month the US Congress passed a bill to ban it in the US unless its owner, Bytedance, sells it. Many parents (including this one) loathe Tiktok for its family-sapping addictive qualities and its ability to fill their kids' heads, and time, with nonsense.

McCourt may fail: various others have expressed interest too. Yet his bid has an interesting element, which links to the subject of this post: how smart and careful breakups of big tech firms can be used to tame toxic content.

Breakup myths

Some people may imagine that breakups are about smashing giant firms into smithereens, pitching the pieces into a mad, heartless neoliberal competitive race to the bottom. They may think of Mickey Mouse as the hapless sorcerer's apprentice in Fantasia: he brings to life a magic broom to fetch water but when it runs amok he splits it into pieces - then faces a worse problem, as many smaller magic brooms create pandemonium.

Instead of breaking up dominant firms, many argue, do something else instead: regulate, build collaborative alternatives, pay workers properly, nationalise them, enforce privacy rules, and so on. And, adding to this, regulators since the 1980s have fallen under a pro-monopoly ideology that has rendered breakups all but taboo.

Yet breakups are not an either/or proposition. In fact, smart breakups can make all these other essential approaches easier.

It’s better to see breakups as a Swiss Army knife: they can be used to pursue many different goals, in many different ways.

A new and relevant paper from the University of Amsterdam, which came out a few days ago, talks of “smart cuts.” Any smart breakup must start with a careful exploration of the firm’s business model, markets, political context and history, to identify the sources of the mischief -- glaring conflicts of interest, say, or dangerous business units -- then cut along the natural fault lines, or carefully remove the offending part(s). Then – crucially – make a plan for what to do with each part.

Companies voluntarily break themselves up all the time, and there are armies of consultants on hand to help: the Chinese internet giant Alibaba, for instance, recently broke itself into six pieces. The problem is, they tend to divest 'non-core' assets: those that aren't essential to the profit-making machine – which usually means keeping the monopoly power intact. We need governments to force breakups in smart ways that go to the heart of the trouble, and with the public interest in mind.

This post looks at one particular set of goals for breakups: whether and how two different kinds of breakup might be used to tame disinformation and hate speech.

The censorship trap

Demagogues, blowhards and corrupt media moguls have spread lies, toxic propaganda and hate speech through history. It's tempting to reach for censorship - and indeed some pernicious forms of speech and content, like child pornography, are (and should be) banned. But who decides what's true and good, and what isn't?

Since the 1980s, for instance, some of the most dangerous economic ideas, especially those of the ‘trickle-down’ variety, have become the conventional wisdom, at least in elite circles. Scorned "populists," when they say popular things such as railing against corrupt vested interests or higher taxes on billionaires, are often right. Who’s to say?

We won't venture here except to note that platforms practice censorship of all kinds already. Through curation and content moderation, each has arbitrary power to decide or influence what we do or don't see. For example, as the Brazilian competition authority CADE is alleging - Google and Meta have been showing lawmakers biased content to influence their votes on legislation to tame social media giants. These arbitrary private speech rules harm pluralism, narrow down what we see online, and curb our rights to freedom of expression or to access information.

The monopoly trap

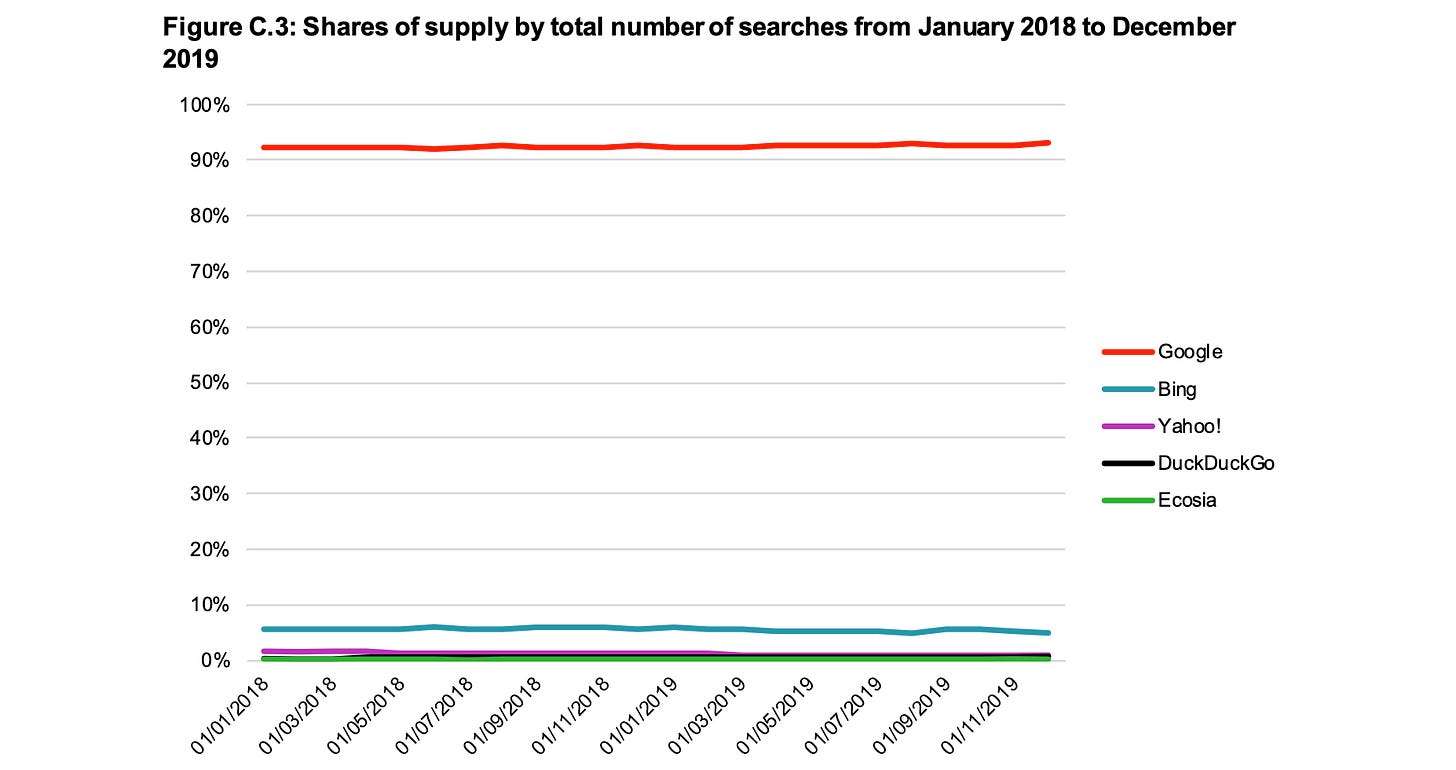

Dominant social media platforms enjoy what we call monopoly power, or 'gatekeeper' power, or chokepoint power. For example, people go to Facebook or Instagram because that's where their friends are, and vice versa: this creates a feedback loop and ‘network effects’ that lock users in. Their presence across a range of services (search, content hosting, instant messaging, etc.) allows the giants to harvest enormous data -- the average European person has their online activity and location exposed nearly 400 times a day -- thus giving them unassailable advantages over any potential competitors. Here's Google's edge, for example.

Once locked in we face a devil's bargain where we must submit to horrible privacy invasions and the reckless sale of our data if we want to connect digitally with our friends and family, or search efficiently. The giants substantially set the bar for the internet, and governments trying to rein in the abuses reach for ineffective remedies: fines, which are treated as little more than a cost of doing business; or trying to change their behaviour, which means playing multi-dimensional whack-a-mole with motivated, powerful, shape-shifting adversaries.

How effectively the big tech firms corrupt public debate is widely debated; what is in no doubt is that their abuses of power amount to, as Cory Doctorow puts it, “real conspiracies” - that inevitably feed the conspiracy theories.

Today's post points to alternative, and potentially powerful approaches, targeting not the content but the monopolistic business models that, among other things, amplify and accelerate hate speech and disinformation, harming democracy, the climate, society, and much else besides.

The goals are to i) reduce overall economic and political power in the system, ii) transform the incentives, and iii) make it easier for democratic states - and parents, and others - to pursue responsible internet use.

Breakups to tame the monopoly trap

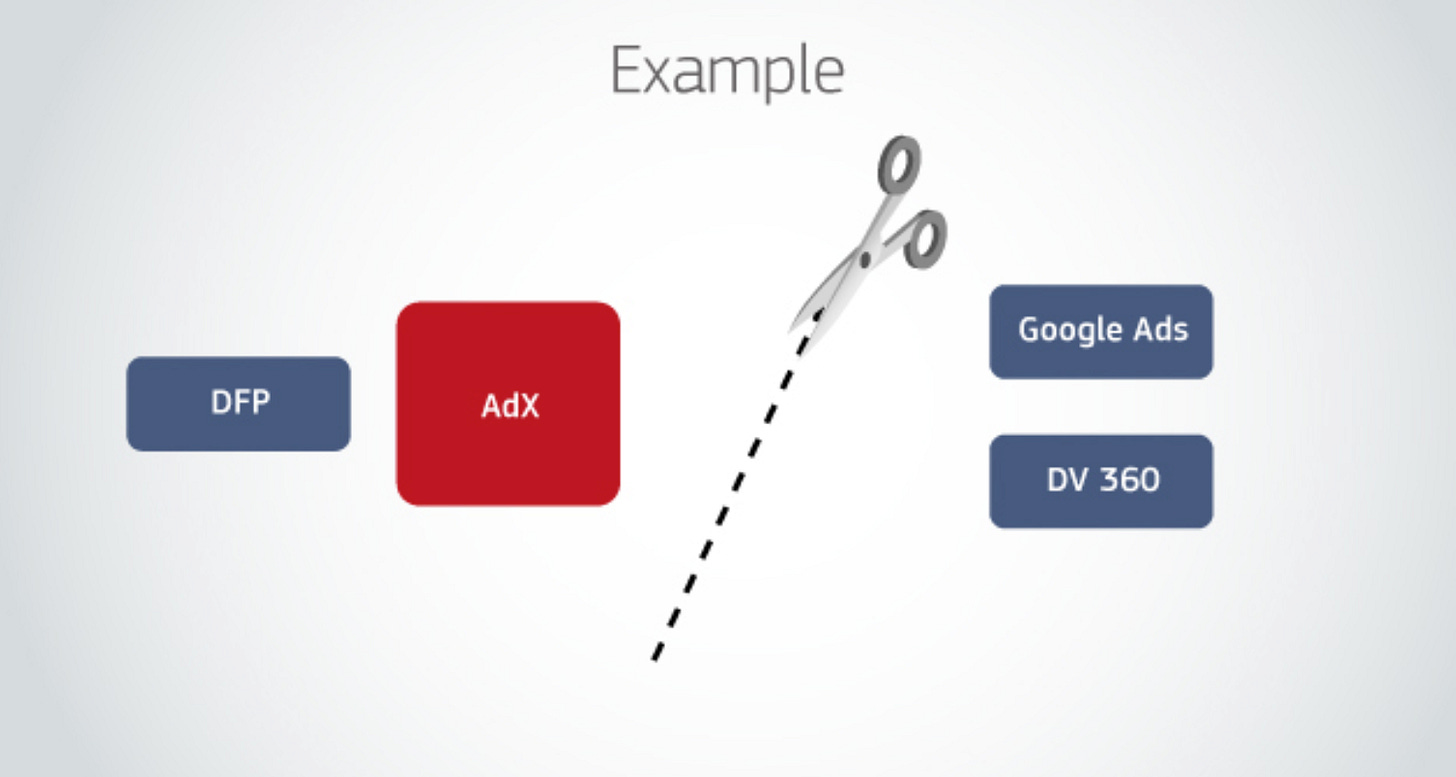

Both the EU Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice (with several states) are right now seeking to target the heart of Google’s democracy-threatening profit machine with a particular breakup approach: a suggestion to remove key elements of the digital advertising technology "stack" that connects online publishers (like newspapers) with advertisers. Google has monopolised this stack, taking an estimated 35 percent cut of all advertising flows.

Here's an official EU image of what *could* happen.

[Update: see this draft paper by Todd Davies and Zlatina Georgieva envisaging stronger medicine, which “would see Google divested of its entire ad-funded business model.]

Given Google's annual quarter-trillion dollar in annual advertising sales, this might release tens of billions to (among others) local news organisations, the cornerstones of our democracies, which are now hemmed in by 'alternative' content and clickbait, and throttled by Google's ability to loot the advertising revenues from content they invest money and shoe leather to create.

Monopoly power corrupts, and is corrupt; and successful monopolies are more powerful than the sum of their individual parts: that is the whole point. So breakups reduce the amount of power in the system: Mickey’s magic brooms will collectively be a lot tamer than the giant rogue broom.

That breakup would be immensely potent. Yet there’s also another measure being discussed now, even more surgically targeted at the toxic-acceleration machines.

Breakups to disrupt the acceleration machines

Social media giants conduct intrusive surveillance on their users, harvesting detailed and intimate data to sell to advertisers. They maximise the harvest by promoting "user engagement" - the more time you spend online clicking furiously, the more data they get. If they can figure out that you have been thinking of buying a high-end sound system, and that you're in a shopping mood right now - well, advertisers will pay well for that. No wonder Google and Meta earned a combined $97 billion from advertising just in the first quarter of this year - on course for a $400 billion in annual advertising sales in 2024, which is worth nearly half the U.S. defence budget.

Toxic and fabricated content, it turns out, usually is (and is designed to be) more engaging than boring true stuff: in one study disinformation was found to spread six times faster than the truth. So the giants use their intimate, often uncanny knowledge of our deep desires to work out which content will keep each one of us, separately, hooked and clicking the longest – and fake and hateful content seems to be particularly effective. So they push us into 'filter bubbles' where like-minded people reinforce each other over angry Youtube rants and clickbait.

A new report just out by Anne Alombert at France’s National Digital Council recounts the many scandals caused by these recommender systems, and argues that they both lie “at the core of the strategies employed by ‘chaos engineers,’ and underpin the economic models of digital giants.” It is automated recommendation that, according to the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), enables ten actors to disseminate 69% of climate-sceptical content on social networks.”

And the combination of these monopoly recommender systems with AI, she notes, will likely worsen the problem in ‘exponential’ ways, with avalanches of toxic content being effortlessly churned out to sow division and flip elections.

Breaking Open the Recommenders

So here's a proposal: separate or “unbundle” hosting services (the place where pictures, videos, links and a variety of content are uploaded and held, for us to view) from curation services (the systems and 'recommender' algorithms that decide which content gets presented to users, when, how often, and in what priority.) You then ensure the giants grant fair and non-discriminatory access to others offering curation services.

Article 19's Maria Luisa Stasi, a leading proponent of this idea, notes:

"The vast majority of social media platforms provide hosting and curation activities as a ‘bundle’. . . are offered together as one.

. . .

This does not need to be the case. It is not irreversible."

This proposal has often been discussed in the context of "interoperability" where tech platforms are required to give access to other firms on fair, non-discriminatory terms. (Inter-operability is a core feature of, for example, the EU's newish Digital Markets Act, or DMA, whose effectiveness remains to be seen.) Such ‘unbundling’ is, as Stasi notes, quite common in networked industries like telecoms.

A stronger and cleaner version - our preference - would also forbid the dominant platform from doing any curation at all: effectively, a full breakup.

If you're doubtful about if this particular would ever happen, let's go back to Frank McCourt's bid for TikTok, via the Financial Times: "McCourt . . . does not want to buy the recommendation algorithm." And the Chinese government has reportedly said it won't allow the sale of Tiktok’s recommender system.

So this breakup will likely happen anyway.

More generally, dominant platforms will never open up their systems voluntarily, as we can see from the “Unfollow Everything” case against Meta platforms: developers are too afraid even to release tools to help tackle these issues, for fear of being sued.

These firms must be broken open, and broken up.

Under this dismantled system, Facebook or Youtube would still show you content, and you could still find what you want and share it with friends, but the giants would no longer decide which content you get to see: instead, a variety of others without monopoly power - we'll get to that - would decide. (This could be extended beyond just speech content: it might be used to prevent Apple recommending Apps in the App Store, or Amazon recommending products on its marketplace – but that’s outside the scope of today’s article.)

Technically, this move is feasible: the internet is a contruction of multiple and mostly seamlessly interconnected systems and protocols, ranging from your wi-fi router to the high-speed auctions used to show you online ads. From a bundled recommender system to a diverse one means rewriting code: for the big tech firms, relatively cheap and easy.

Is competition and choice enough, though?

In the competition policy world, many would couch this breakup as being "pro-competitive." We don't entirely disagree, and this is often the legal justification needed to get things done. But competition is not enough on its own, or may not always be the right maxim: while it can bring benefits, it can be harmful too, especially amid lax regulation or weak enforcement.

With many different 'recommender' systems, Mickey Mouse still faces all those smaller but potent magic brooms. On the plus side, 'recommenders' might compete for users by emphasising probity and child safety. By contrast, they might compete for advertisers by promising deeper surveillance of users and thus promoting more toxic content.

But here's the thing. By transforming today’s accelerators backed by monopoly power and enforced devil's bargains, into a system with choice, multiple benefits emerge.

First, choice lets users select better algorithms and recommenders. Parents could, for instance, only allow their 12-year old a system geared to protect children and teens, or even more tailored ones to encourage learning and civic values. That would be popular, not least with this parent. One could imagine "public interest", open-source and publicly funded algorithms of many kinds, as Alombert and Stasi discuss: all set up in ways that users know won't hoover up data on their health status or sexual preferences and flog it to all comers.

Recommenders might become a bit like newspapers: offering curated collections of articles, paid for with advertising or otherwise, catering to different tastes, Jazz, cooking, fishing, say, with room for publicly owned, or public-interest bodies too – perhaps a BBC or Deutsche Welle recommender might be tasked with (among other things) safeguarding democracy.

This proposal would also, like the adtech breakup above, sharply reduce the profits and power in the system, reducing the giants' power to block democratic change.

And here’s another important angle. In the current monopolised situation, regulators can't shut down a lone (rogue, say Facebook's) monopoly recommender system, or impose a fine massive enough to change its behaviour meaningfully, without radically disrupting a big chunk of the internet, possibly causing social unrest which the giants could weaponise in their favour. These firms are now too big to fail. But with real choice, regulators can do exactly that, shutting down or disruptively fining a bad actor while knowing that users and advertisers can easily migrate to the alternatives. A system with choice is resilient, with no single point of failure, holding us all hostage.

As with anything online, of course, there many complexities and challenges (see e.g. Stasi on pp157-174 here, or pp 16-17 here.) How would the hosting platform share advertising revenues with recommenders? Would diverse recommenders be as as secure? How should regulators deal with the rump hosting platform after breakup? Do most people really want to move away from clickbait or toxic content? Where will governments find the will-o-the-wisp called political will to force this? If enough people get behind ideas such as "Break Open Big Tech", much becomes possible.

Beyond these breakups

The Swiss Army knife of breakups could be deployed in several other ways too. All the big tech firms are conglomerates with many disparate parts, faultlines and conflicts of interest that could be operated on to reduce the power in the system and eliminate conflicts. Giant platforms could be divided from their cloud services; marketplaces could be separated from retail divisions or distribution arms, Facebook could be separated from Whatsapp and Instagram, and more. On breaking up Amazon, here is Lina Khan’s 2017 classic, here is LobbyControl’s more recent exploration, from a more non-US perspective; and the University of Amsterdam paper cited above suggests particular forms of ‘smart cuts’.

We plan soon to publish a report about targeted breakups beyond big tech, so as to be able to tackle some of the gravest problems the world faces. Watch this space.