Digital entertainment risks falling further into the hands of private interests as Netflix and Paramount wrestle for control over Warner Bros

Hello and welcome to the latest edition of The Counterbalance newsletter. This week we’re taking a look at a potential Warner Bros takeover.

The media world is watching as Netflix and Paramount Skydance race to seize control of Warner Bros Discovery, and the outcome of any potential takeover threatens to reshape what we watch, how content is made, and crucially: who controls the cultural significance and impact of a massive part of the entertainment industry.

Last week Netflix stunned Hollywood when it struck a deal to acquire WBD’s film and TV studios, including its streaming business and massive library of franchises from Harry Potter to Game of Thrones. The deal, valued at roughly $72 billion, threatens to concentrate an enormous amount of cultural and commercial power.

Shortly after, Paramount Skydance muddied the waters with a hostile all-cash bid of over $108 billion for WMB, offering $30 per share for the entire company.

So why does this wrestling match between Netflix and Paramount matter? Regardless of who may land a deal, the potential consolidation raises deep concerns for competition as the markets affected reach tipping point, content diversity, and ultimately risks breaking the levee in an already highly concentrated entertainment sector.

If Netflix prevails, it would combine its global streaming dominance with some of the most influential movie and TV brands of the past century. That could lock in a new giant controlling what stories get told, how they are distributed, and what mainstream entertainment culture looks like for decades into the future.

In a recent post on LinkedIn, CCO of B2B firm Shake Dani Markovits said the potential Warner acquisition could mark the end of Netflix as a tech company, effectively repurposing it as a “licensing monopoly”.

“One thing is for certain, if regulators approve, Hollywood will never look the same,” he added.

This sentiment echoes wider concerns. For example, theatre chains in the US have warned that the proposed Netflix deal would slash US and Canadian box office revenue by 25% if Warner Bros films skip theatres for streaming.

“We believe that a vibrant, competitive industry — one that fosters creativity and encourages genuine competition for talent — is essential to safeguard the careers and creative rights of directors and their teams,” said the Directors Guild of America.

In Europe, there will also be concerns that any merger will likely hike prices for its own consumers, however it is not clear that the impact on workers will be directly considered at the EU level — a reminder that EU merger guidelines must be revisited.

The streaming-first logic that is integral to Netflix could further marginalise cinemas and broader film culture. Predictably, a merged Netflix-WBD entity would prioritise volume, convenience and scale at the direct expense of local, community-focused alternatives or groups that are frequently under-represented in the sector.

This problem has already materialised in alarming ways in the music sector, another entertainment pocket increasingly defined by the streaming economy.

Smaller artists representing minority cultures are losing control over their creative output amidst an increasing power imbalance brought about by the rise of streaming giants like Spotify and YouTube.

According to a 2024 study conducted in The Netherlands, which studied Turkish-origin users and Dutch users, platforms like Spotify were found to have a “generic popularity bias,” exposing the need to “improve the representation of users with non-mainstream music preferences.” The study found that this kept users “in a repetitive loop that hinders the exploration of new music.”

Thus, media and streaming platforms are no longer just for entertainment, but they also influence politics, social norms and public discourse. When fewer companies control more content, there is an increased risk that a small group of powerful corporate executives in the entertainment sector (and their political backers) will decide what voices get amplified and which are silenced.

With Paramount’s arrival to the scene, the battle for WBD has also quickly entered mainstream politics. US President Donald Trump weighed in and warned that Netflix’s proposed acquisition “could be a problem”, that Netflix has a “very big market share” which could “go up by a lot” if the deal were to go ahead, adding he would be personally involved in approval.

Trump’s words may first come across as a welcome sign for anti-monopoly advocates, but it is important to remember that Paramount’s backers are deeply connected to the President and his political interests. [And that assessment of the impacts of the merger should be the preserve of the technical competition enforcement agencies.]

“The argument is that David Ellison, the chief executive of Paramount, wants to build an evil media empire using his father’s money and to gun CNN,” wrote Tim Wu in the New York Times. The Paramount pursuit of WBD is also fuelled by a private equity firm led by son-in-law Jared Kushner, deepening ties to the White House, reminding us yet again of the high stakes political dimension at play.

There is always the possibility that regulators could block the deal. But precedent suggests this is unlikely in either the US or the EU. In the EU there is the added complexity of blocking a deal between two purely US companies, in an already tense geopolitical context defined by tariffs and trade wars. And while the deal could be reviewed in the UK, the CMA may choose to deploy its new approach of deferring to other competition agencies when the market is broader than just the UK, and thus avoid political ire at home and in the US.

It seems more likely that to prevent the newly merged entity from having a monopoly over content, regulators will favour remedies over blocking the deal. They could also impose a demand to maintain film and TV licensing agreements, or a forced divestiture of operations like HBO Max.

Moreover, AI concerns must be added to the pot as there is a very real risk that a newly merged Netflix entity could train its AI model on a huge, sprawling library of newly acquired content.

In short, regulators on both sides of the Atlantic must treat this merger not simply as a business transaction but evaluate the risks from cultural and societal perspectives. The impacts on competition, innovation, independent cinema, content diversity and political discourse could reshape the creative sphere for a generation or more.

Soundbite of the week: Google’s stranglehold on Europe must be stopped

The Balanced Economy Project has this week joined over 70 press freedom groups, businesses, experts and think tanks calling on the European Commission to reject Google’s bid to retain its monopoly grip on Europe’s €120 billion adtech market.

Our letter points out that behavioural remedies have consistently failed to rein in Google’s unjust dominance of European markets, and that only a structural remedy will provide a solution to Google’s continued unjust dominance.

“The health of European journalism and democracy is at stake…only divestment of Google’s adtech monopoly will safeguard Europe’s democracy, defend its sovereignty, and protect citizens and publishers from Google’s predations,” our letter reads, which you can access here.

Weekly highlight: Big Tech’s continued encroachment into the UK

The UK’s Tech Secretary Liz Kendall is travelling to California for a two-day visit, per POLITICO. While she is there, she will be “bigging-up the UK’s tech partnership with the US,” including a fireside chat alongside Business Secretary Peter Kyle and Google President Ruth Porat.

Her visit coincides with a recently signed MoU between Google DeepMind and the UK government, which Prime Minister Keir Starmer described as “national renewal in action.”

The deal — alongside Kendall’s US trip — is a stark reminder that while eyes turn to a potential Netflix deal or the latest clashes between Europe and Google, Big Tech continues its encroachment into UK politics.

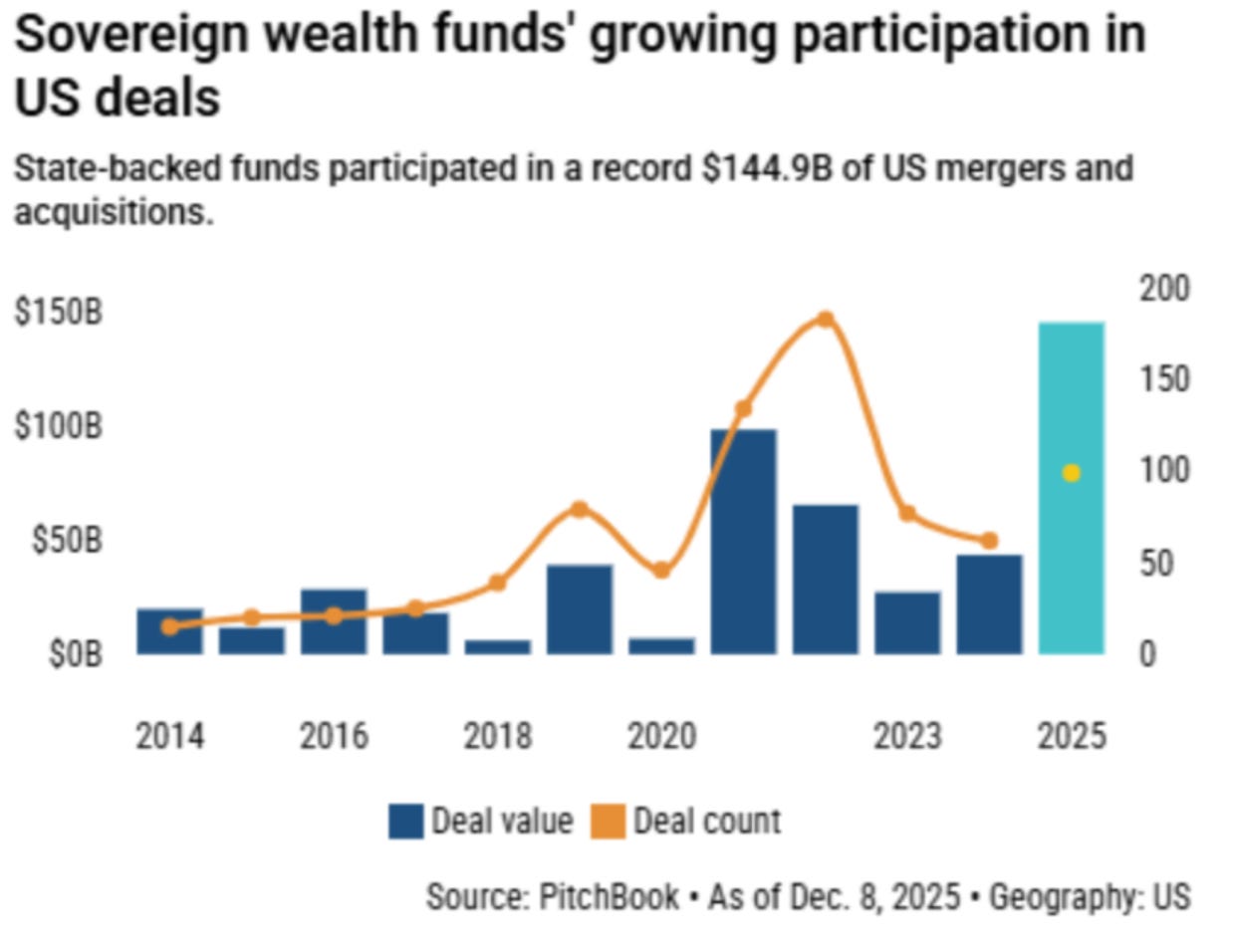

Data mining: Sovereign wealth funds’ growing participation in US deals

State-backed funds have participated in just under $145 billion worth of US mergers and acquisitions in the last decade, per data from PitchBook.

The Paramount saga is the second time that has linked the President’s son in law, Jared Kushner, to a marquee deal after his private equity fund Affinity Partners was at the heart of a deal to buy Electronic Arts, the gaming company behind FIFA.

The increasing involvement of sovereign wealth funds would set off alarm bells for all, as it signals a deepening fusion between state-backed wealth, politically connected capital, and the most powerful media and technology assets in the world.

The Counterbalance will pause for the Christmas holidays and will return to your inboxes in the new year. Until then, feel free to send any thoughts and feedback to scott@balancedeconomy.org.

Jesus. I already Don't Stream and this corks it. I'm un-subscribing from all these financialists who'd 'own' our every activity short of, ehm, tooth-brushing. If you haven't already tracked down a working DVD player from your neighborhood charity shop, I'd start looking. And while you're there, root through the bin of other people's old DVD movies and music. There's a trove of material there for a buck a disc.

Tim Long, Just Up the Hill from Lock 15.