Too big to bar: the power of private capital

Hello and welcome to the latest edition of The Counterbalance newsletter. This week we’re taking a look at how one big bank is shaping the rules of the game in its favour.

Earlier this month, a Credit Suisse-linked entity pleaded guilty to criminal charges in the United States.

Credit Suisse Services AG pleaded guilty and was sentenced on May 5th, 2025 to conspiring to hide more than $4 billion from the IRS in at least 475 different offshore accounts. The unit was imposed a fine of over $510 million.

The guilty plea from the Swiss bank is a result of a multiyear investigation on behalf of US law enforcement agencies, although the scandal facing Credit Suisse — which was acquired by UBS in 2023 — is not an isolated incident.

Over the last decade, the Swiss banking stalwart has stumbled through a litany of compliance scandals, including $10 billion worth of exposure to Greensill Capital, as well as the 2022 “Suisse secrets leak” which exposed billions of dollars in bank accounts linked to an array of bad actors.

Credit Suisse’s poor track record teaches us an important lesson about big capital and unchecked corporate power. And the real scandal begins on May 5th, the same day the bank pleaded guilty to criminal charges.

.In the wake of the bank’s guilty plea, the US’s top securities watchdog the Securities and Exchange Commission granted a temporary waiver allowing specific UBS-affiliated entities to continue investment advisory and underwriting services.

Thus, this is no longer just a story about big bank corruption. It’s a story about how dominant power and concentrated capital creates a separate tier of justice.

“"The game is rigged, and the cards are crooked,” said Paul Morjanoff, financial crime expert at Financial Recovery and Consulting Services.

In US law, a criminal conviction can lead to automatic disqualification from certain financial activities, but the law also provides the SEC with discretion to grant exemptions, including when disqualifying dominant banks — like Credit Suisse — can cause wider financial instability.

Credit Suisse’s waiver is not just one isolated legal workaround, either. It is a case study in how power shields institutions from consequences, and maintains a narrative that prevents society from holding big actors fully to account.

While the world’s media coverage of the May 5th criminal conviction focused on a sense of corruption in a narrow sense, what we are actually dealing with is a system where scale itself is a defence against consequences.

The firm’s strategic dominance in financial markets makes disqualification from regulated activity — however warranted under law — untenable. In other words, yes, corruption and illicit finance is seriously grave and consequential, but the root issue here is the size and power which facilitates bad behaviour and criminal activity in the first place.

Granted, the SEC has not bluntly said “Credit Suisse is too big to disqualify,” but the logic for waiver decisions speaks for itself. This is the essence of big capital power in finance. It is not just about market share, but about structural indispensability.

In a previous version of The Counterbalance, we called on US regulators to come down hard on Google, not least to signal that the tech sector should not fall prey to monopoly power in the same way traditional financial markets have, where large institutions were allowed to become so big their existence now presents a permanent risk to financial stability.

The Credit Suisse story is a glaring example of this in practice. Without dismantling big capital, regulators can only continue to offer piecemeal consequences for bad corporate behaviour.

Weekly highlights:

Media measurement company Comscore was slapped with an antitrust lawsuit this week when Atlas – film distribution firm — accused it of leveraging a monopoly on data related to box office numbers in order to “suppress competition.” Atlas adds the move from Comscore forced it to shut down a software app named CinemaCloudWorks. Atlas is seeking a preliminary injunction that would require Comscore to reinstate access to aforementioned data and seeks undisclosed monetary damages.

A note from Indonesia: Indonesia antitrust agency has begun researching potential risks associated with a possible merger between Grab and GoTo, two major tech companies in the region. While the two parties have yet to announce merger plans officially, the possibility of the merger has been widely reported.

Soundbite of the week: Apple angers US judge:

Apple has raised the ire of US District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers, who directed the tech giant to appear in court and justify why it felt it should not face penalties for an alleged violation relating to an antitrust dispute with Epic Games.

In a court order filed this week in the US District Court for the Northern District of California, Judge Rogers demanded an Apple official “personally responsible for compliance” appear in court if Apple and Epic Games do not file a joint notice confirming the issue is resolved.

She also slammed Apple’s vice president of finance, Alex Roman, alleging “to hide the truth…Roman…outright lied under oath.”

Data mining: European tech funding resurgence

If you have been a longstanding subscriber to The Counterbalance, you will know we like to keep a sharp eye on the venture capital markets.

Venture capital often fuels monopolisation by funding the acquisition of small, would-be competitors and consolidating them under a single corporate umbrella. This strategy rapidly concentrates market power, reduces competition, and sometimes can lead to disastrous consequences in societies’ crucial infrastructure.

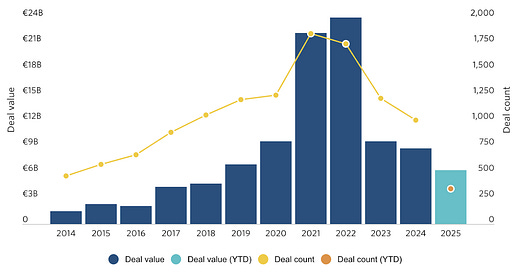

In Europe, venture capital funds are back pouring into the fintech industry and are set to outpace investment figures from 2024, per data from PitchBook. Low interest rates and inflation have prompted investors to return to the table to the tune of over €6.3 billion so far.

This equates to more than 70% of last year’s annual deal value total, and we aren’t even halfway through the year.

But while these figures may be celebrated by fintech industry insiders, the problem with concentration is that it risks undermining the core dynamic of a competitive market, slowing innovation rather than speeding it up.

European tech funding surges and is on pace to overtake 2024 figures

The Counterbalance is published every Thursday. Please send any thoughts and feedback to scott@balancedeconomy.org.